Last month I traveled to Florida with my wife and daughter to spend Christmas with my parents at their house near Orlando. As part of that trip we drove to Streamsong, a new resort about one hour straight east of Tampa, to play some golf, stay at the lodge, and get a tour of the resort from architect Alberto Alfonso. The visit is documented in three posts, one focusing on the lodge, one on the clubhouse, and one on the Blue golf course.

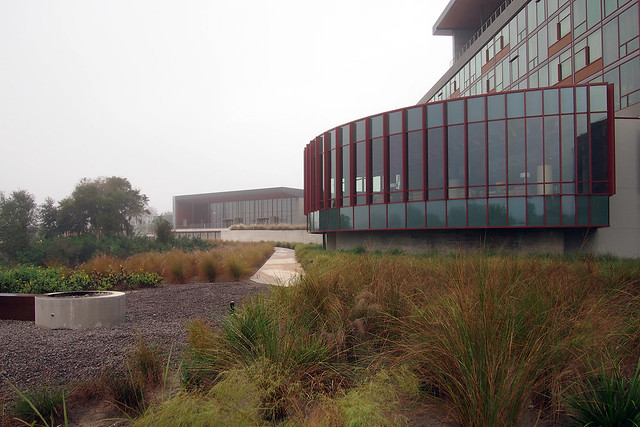

[A distant view of the golf courses from the roof of the lodge | All photographs by John Hill unless noted otherwise; click my photos to see larger versions at Flickr.]

As mentioned yesterday in my post on the clubhouse, the trip from the lodge to the clubhouse is a good two miles, reached by shuttle on a winding road. Therefore the only place to grasp the presence of the golf courses from the lodge is from the roof, where the general character of the courses is apparent. While trees are visible in the foreground in the photo above, the distant courses are free of trees, with dunes interspersed with bunkers and lush fairways. The 36 holes courses appear to be lifted to the center of Florida from the shores of Scotland.

[Scanned map of Blue and Red courses - click to enlarge]

Two 18-hole courses have graced Streamsong since 2012, the Blue, credited to Tom Doak of Renaissance Golf Design, and the Red, credited to Coore + Crenshaw. My dad and I only had enough time to play one round of golf, so choosing between two courses that are already highly respected and rated was not easy. Reports indicate that the divisions between who designed what is not clear, as each designer provided input on the other designer's course. And the layout – a kind of yin-yang, with the Red and Blue intertwining in parts – reinforces this blurriness. Nevertheless, each course is played separately, and while the Red course is rated higher on most best-of lists (the Blue not far behind in most cases), I opted to play the Blue course, mainly because I wanted to see how Doak's design related to his writing, primarily The Anatomy of a Golf Course (Burford Books, 1992) that I had read last year.

Before designing golf courses, first with Pete Dye and then on his own, Doak received a landscape architecture fellowship and traveled the globe to visit great courses. Out of that on-the-ground research came the much lauded Confidential Guide to Golf Courses (long hard to find, the book has been getting an update in five volumes; the first title, on the golf courses of Great Britain and Ireland, was just published on his company's website) and later the Anatomy book. These highly opinionated works lay out Doak's approach to design, which, to put it simply, prizes traditional links courses and the type of play they embody, which is on the ground as well as in the air. His subsequent courses have met with much praise from critics and golfers, especially Pacific Dunes in Oregon, and have greatly influenced the recent push toward more "natural"-looking, links-style courses. The visit to Streamsong would be my first chance to play one of his courses.

[Two views of the Red course's 1st hole as seen from the clubhouse]

While seated on the clubhouse's terrace (the location of the clubhouse is visible in the lower-right quadrant of the map above, just right and down from the "B" circle), where I had lunch with my family before the round of golf, I could only glimpse the Red course, specifically the first hole, which requires a shot over water to a fairway just visible between some of the dunes that were created from the sand spoils of the former phosphate mine. The Blue course, on the other hand, starts from atop a 75-foot-high dune that plays to the west, out of sight and away from the clubhouse. From this perch are some great views: of the clubhouse, of the Blue course's "signature" 7th hole, and of the Mosaic Company's 16,000 acres in all cardinal directions.

[A view toward the 7th hole of the Blue course from the elevated 1st tee]

Before delving into some detail on the course and a few of its holes, it's worth pointing out where I came from and how the Blue course differs from the courses I've played. Having played on the golf team in high school, caddied for about six summers in high school and college, and liked the sport enough that I briefly aspired to design golf courses as a career, I had played a fair number of courses, most of them in the Chicago area in the 1990s. The majority of the courses I encountered were what could be described as modern North American courses, meaning they had raised tee boxes, fairways lined by rough and trees, pea-shaped bunkers in strategic areas alongside fairways and around greens, the occasional man-made water hazard, and gently undulating greens. Not all of the courses I played were necessarily good, but good or bad they tended to follow these basic characteristics.

The Blue course is different than this "norm" in just about every way: The tees are only sometimes raised but almost always an extension of the grass around the previous green; the fairways are very wide, lined with long grasses and scrub (with no rough in sight); the bunkers are abundant and irregular, as if shaped by wind; the water hazards are few but they are sizable and appear to be naturally occurring; and the greens have some pretty severe undulations that can be helpful or nightmarish depending on the pin position. Many more courses in the United States are being designed and built in this manner, which approximates the wind-shaped links golf of the British Isles, even if, in the case of Streamsong, the ocean is a 90-minute drive away and bulldozers were necessary to create the rugged landscape. The differences between the Blue course and my experiences meant some adjustments to my gamer were necessary, but I also realized, having lost only two balls the whole day, that mishits and wayward shots resulted in penalties much less than they did in good fortune.

[One of the fairways on the front nine of the Blue course]

[An approach to a green on the front nine; note the yellow flag in the middle-right section of the photo, just below the flat horizon.]

As mentioned, the 1st tee of the Blue course sits atop a 75-foot-high dune, the tallest spot on the golf course. This position, and the fact the drive does not need to carry a water hazard as on the Red course's opener, means the forgiving nature of the course is evident from the get-go. Heck, I topped my drive about 50 yards (I chalk this up to not having warmed up between lunch and tee-off, and to playing only two or three times a year), but the ball still reached the fairway. These pieces of well manicured landscape, which are like islands of trimmed grass on most North American courses, are everywhere at Streamsong, leaking around the dunes and bunkers like a viscous fluid that connects each tee to its green, each green to its next tee, and in some cases one fairway to the one next to it. The effect isn't jarring so much as refreshing, because even as the sizable bunkers and their high lips like to devour golf balls, in most cases a near miss means the next shot will be hit from the fairway, not long grass.

[A view of the 7th green from the back tees]

[A view of the 7th green from the front tees]

Perhaps it's because of the wide and flowing fairways that the most memorable hole on the golf course is the par-3 7th. (This isn't to say the other holes aren't memorable, but they blur together in my memory so much that, for example, I don't recall which holes are documented in the front-nine photos shown above.) For here is a hole with a distinct break between tee and green. In between is a pond – the same pond that nestles next to the clubhouse – that is traversed by an arcing wooden walkway that seems to say, "There are no straight lines in golf!" The large dunes that act as a backdrop to the green and separate it from the Red course don't hurt the hole's picture postcard quality.

Within the triumvirate of schools of golf design – the "heroic," the "penal" and the "strategic" – forced carries, typically over water but sometimes sand or scrub, fall into the penal. These broad categories sometimes apply to whole courses, but more often to individual holes, or even to particular hazards on a hole, such that of one type can be found mixed along with others within a course. The Blue course is a great mix of the heroic, the penal and the strategic. The 7th hole is penal because a topped shot (like my 50-yard drive on the first hole) or some other wayward shot is penalized, although one hit over the water is not, to the same degree at least. Other holes on the Blue course are heroic, such as the long par-4 8th, which features a fairway split into two landing areas by a lone bunker that sits like a bellybutton in the middle of the fairway; hitting to the right makes the hole longer but safer, while hitting left of it turns the dogleg into a shorter straight hole that requires a more difficult second shot over a pond next to the green.

[Looking at some front-nine holes from the tee of the 13th hole; the tall dune is (I think) the first tee.]

[A similar view, but from the 13th green (note the matching tall dune)]

If only one of the three schools were applied to the Blue course it would be the strategic, which Doak discusses in The Anatomy of Golf like this: "Difficult hazards, which the golfer may label penal, are the essence of interesting golf, and nowhere more so than in the strategic school, where there ought to be a distinct penalty for the golfer who has failed to heed the hazard after being given plenty of room to do so." As the two photos above and the two photos below attest, there are plenty of hazards on the Blue course, but there is also plenty of space, of fairway around the hazards. The 13th hole, for example, is a short par 4 that plays alongside a pond for most of its length, but the fairway billows out away from the water to give the timid golfer a safe route. The bunkers that cross the fairway on the long par-4 18th hole, on the other hand, are so far short of the green that they are out of play for scratch golfers, but they are in play for short hitters; lay up from them on the second shot and the hole plays as a short par 5, but try to go for the green in two and your ball may be devoured by the hazard (note the pink ball in the bunker in the second photo below). Nearly every hole has a safe route that can be found, either by luck, by accident, with help from the complimentary Players' Book, or with help from the caddy.

[Approach to the 18th hole on the Blue course with the clubhouse in the distance]

[View toward the Red course from the fairway of the Blue course's 18th hole]

"Did you say caddy?" Yes, I did. One of the distinguishing characteristics of Streamsong is the requirement to have a caddy, be it if you're walking or if you take a cart. The club and the designers prefer the former, per their "walking philosophy," such that walking is the only option from January to April, and the rest of the year carts are allowed at only certain times of the day. Having to carry my own bag when I played in high school, and never having owned a car for that matter, I'm a fan of walking. I like to I think walking the course readies the mind better for shots (the time it takes to approach the ball is longer when walking than by cart, but that time can be spent thinking about the next shot); and it is better for the body. And having caddied all those years ago, I am appreciative of the job, especially on a course like Streamsong Blue, which has a few blind shots and those killer greens (our caddy helped me sink a couple curling putts, one of them from about 50 yards away for my only birdie of the round).

Both the caddy requirement and the walking philosophy root Streamsong in golf traditions that go hand in hand with what Doak espouses in The Anatomy of a Golf Course and in his Blue course design, namely links-style golf that allows golfers of varying abilities to enjoy themselves. I can't imagine playing the Old Course at St. Andrew's (and hopefully someday I will play it) without a caddy, given the undulations, bounces, pot bunkers and hidden hazards. I also can't imagine scoring as well as I did on the Blue course without our caddy. Links golf – be it on the Scottish coast or in the middle of Florida – benefits from somebody with knowledge of a course.

Likewise, a golf course is best traversed by foot, along the fairways rather than along the cart paths. Even though my dad and I took a cart, the beauty of the course should be evident in the photos I took, photos that only capture a fraction of what Doak, Coore and Crenshaw have created in one of the most unlikeliest of settings.

[Streamsong logo on a wall at the lodge]

This wraps up my three-part tour of Streamsong Resort. See also the first installment on the lodge and the second installment on the clubhouse. Head over to Flickr to see more photos of Streamsong.

[A distant view of the golf courses from the roof of the lodge | All photographs by John Hill unless noted otherwise; click my photos to see larger versions at Flickr.]

As mentioned yesterday in my post on the clubhouse, the trip from the lodge to the clubhouse is a good two miles, reached by shuttle on a winding road. Therefore the only place to grasp the presence of the golf courses from the lodge is from the roof, where the general character of the courses is apparent. While trees are visible in the foreground in the photo above, the distant courses are free of trees, with dunes interspersed with bunkers and lush fairways. The 36 holes courses appear to be lifted to the center of Florida from the shores of Scotland.

[Scanned map of Blue and Red courses - click to enlarge]

Two 18-hole courses have graced Streamsong since 2012, the Blue, credited to Tom Doak of Renaissance Golf Design, and the Red, credited to Coore + Crenshaw. My dad and I only had enough time to play one round of golf, so choosing between two courses that are already highly respected and rated was not easy. Reports indicate that the divisions between who designed what is not clear, as each designer provided input on the other designer's course. And the layout – a kind of yin-yang, with the Red and Blue intertwining in parts – reinforces this blurriness. Nevertheless, each course is played separately, and while the Red course is rated higher on most best-of lists (the Blue not far behind in most cases), I opted to play the Blue course, mainly because I wanted to see how Doak's design related to his writing, primarily The Anatomy of a Golf Course (Burford Books, 1992) that I had read last year.

Before designing golf courses, first with Pete Dye and then on his own, Doak received a landscape architecture fellowship and traveled the globe to visit great courses. Out of that on-the-ground research came the much lauded Confidential Guide to Golf Courses (long hard to find, the book has been getting an update in five volumes; the first title, on the golf courses of Great Britain and Ireland, was just published on his company's website) and later the Anatomy book. These highly opinionated works lay out Doak's approach to design, which, to put it simply, prizes traditional links courses and the type of play they embody, which is on the ground as well as in the air. His subsequent courses have met with much praise from critics and golfers, especially Pacific Dunes in Oregon, and have greatly influenced the recent push toward more "natural"-looking, links-style courses. The visit to Streamsong would be my first chance to play one of his courses.

[Two views of the Red course's 1st hole as seen from the clubhouse]

While seated on the clubhouse's terrace (the location of the clubhouse is visible in the lower-right quadrant of the map above, just right and down from the "B" circle), where I had lunch with my family before the round of golf, I could only glimpse the Red course, specifically the first hole, which requires a shot over water to a fairway just visible between some of the dunes that were created from the sand spoils of the former phosphate mine. The Blue course, on the other hand, starts from atop a 75-foot-high dune that plays to the west, out of sight and away from the clubhouse. From this perch are some great views: of the clubhouse, of the Blue course's "signature" 7th hole, and of the Mosaic Company's 16,000 acres in all cardinal directions.

[A view toward the 7th hole of the Blue course from the elevated 1st tee]

Before delving into some detail on the course and a few of its holes, it's worth pointing out where I came from and how the Blue course differs from the courses I've played. Having played on the golf team in high school, caddied for about six summers in high school and college, and liked the sport enough that I briefly aspired to design golf courses as a career, I had played a fair number of courses, most of them in the Chicago area in the 1990s. The majority of the courses I encountered were what could be described as modern North American courses, meaning they had raised tee boxes, fairways lined by rough and trees, pea-shaped bunkers in strategic areas alongside fairways and around greens, the occasional man-made water hazard, and gently undulating greens. Not all of the courses I played were necessarily good, but good or bad they tended to follow these basic characteristics.

The Blue course is different than this "norm" in just about every way: The tees are only sometimes raised but almost always an extension of the grass around the previous green; the fairways are very wide, lined with long grasses and scrub (with no rough in sight); the bunkers are abundant and irregular, as if shaped by wind; the water hazards are few but they are sizable and appear to be naturally occurring; and the greens have some pretty severe undulations that can be helpful or nightmarish depending on the pin position. Many more courses in the United States are being designed and built in this manner, which approximates the wind-shaped links golf of the British Isles, even if, in the case of Streamsong, the ocean is a 90-minute drive away and bulldozers were necessary to create the rugged landscape. The differences between the Blue course and my experiences meant some adjustments to my gamer were necessary, but I also realized, having lost only two balls the whole day, that mishits and wayward shots resulted in penalties much less than they did in good fortune.

[One of the fairways on the front nine of the Blue course]

[An approach to a green on the front nine; note the yellow flag in the middle-right section of the photo, just below the flat horizon.]

As mentioned, the 1st tee of the Blue course sits atop a 75-foot-high dune, the tallest spot on the golf course. This position, and the fact the drive does not need to carry a water hazard as on the Red course's opener, means the forgiving nature of the course is evident from the get-go. Heck, I topped my drive about 50 yards (I chalk this up to not having warmed up between lunch and tee-off, and to playing only two or three times a year), but the ball still reached the fairway. These pieces of well manicured landscape, which are like islands of trimmed grass on most North American courses, are everywhere at Streamsong, leaking around the dunes and bunkers like a viscous fluid that connects each tee to its green, each green to its next tee, and in some cases one fairway to the one next to it. The effect isn't jarring so much as refreshing, because even as the sizable bunkers and their high lips like to devour golf balls, in most cases a near miss means the next shot will be hit from the fairway, not long grass.

[A view of the 7th green from the back tees]

[A view of the 7th green from the front tees]

Perhaps it's because of the wide and flowing fairways that the most memorable hole on the golf course is the par-3 7th. (This isn't to say the other holes aren't memorable, but they blur together in my memory so much that, for example, I don't recall which holes are documented in the front-nine photos shown above.) For here is a hole with a distinct break between tee and green. In between is a pond – the same pond that nestles next to the clubhouse – that is traversed by an arcing wooden walkway that seems to say, "There are no straight lines in golf!" The large dunes that act as a backdrop to the green and separate it from the Red course don't hurt the hole's picture postcard quality.

Within the triumvirate of schools of golf design – the "heroic," the "penal" and the "strategic" – forced carries, typically over water but sometimes sand or scrub, fall into the penal. These broad categories sometimes apply to whole courses, but more often to individual holes, or even to particular hazards on a hole, such that of one type can be found mixed along with others within a course. The Blue course is a great mix of the heroic, the penal and the strategic. The 7th hole is penal because a topped shot (like my 50-yard drive on the first hole) or some other wayward shot is penalized, although one hit over the water is not, to the same degree at least. Other holes on the Blue course are heroic, such as the long par-4 8th, which features a fairway split into two landing areas by a lone bunker that sits like a bellybutton in the middle of the fairway; hitting to the right makes the hole longer but safer, while hitting left of it turns the dogleg into a shorter straight hole that requires a more difficult second shot over a pond next to the green.

[Looking at some front-nine holes from the tee of the 13th hole; the tall dune is (I think) the first tee.]

[A similar view, but from the 13th green (note the matching tall dune)]

If only one of the three schools were applied to the Blue course it would be the strategic, which Doak discusses in The Anatomy of Golf like this: "Difficult hazards, which the golfer may label penal, are the essence of interesting golf, and nowhere more so than in the strategic school, where there ought to be a distinct penalty for the golfer who has failed to heed the hazard after being given plenty of room to do so." As the two photos above and the two photos below attest, there are plenty of hazards on the Blue course, but there is also plenty of space, of fairway around the hazards. The 13th hole, for example, is a short par 4 that plays alongside a pond for most of its length, but the fairway billows out away from the water to give the timid golfer a safe route. The bunkers that cross the fairway on the long par-4 18th hole, on the other hand, are so far short of the green that they are out of play for scratch golfers, but they are in play for short hitters; lay up from them on the second shot and the hole plays as a short par 5, but try to go for the green in two and your ball may be devoured by the hazard (note the pink ball in the bunker in the second photo below). Nearly every hole has a safe route that can be found, either by luck, by accident, with help from the complimentary Players' Book, or with help from the caddy.

[Approach to the 18th hole on the Blue course with the clubhouse in the distance]

[View toward the Red course from the fairway of the Blue course's 18th hole]

"Did you say caddy?" Yes, I did. One of the distinguishing characteristics of Streamsong is the requirement to have a caddy, be it if you're walking or if you take a cart. The club and the designers prefer the former, per their "walking philosophy," such that walking is the only option from January to April, and the rest of the year carts are allowed at only certain times of the day. Having to carry my own bag when I played in high school, and never having owned a car for that matter, I'm a fan of walking. I like to I think walking the course readies the mind better for shots (the time it takes to approach the ball is longer when walking than by cart, but that time can be spent thinking about the next shot); and it is better for the body. And having caddied all those years ago, I am appreciative of the job, especially on a course like Streamsong Blue, which has a few blind shots and those killer greens (our caddy helped me sink a couple curling putts, one of them from about 50 yards away for my only birdie of the round).

Both the caddy requirement and the walking philosophy root Streamsong in golf traditions that go hand in hand with what Doak espouses in The Anatomy of a Golf Course and in his Blue course design, namely links-style golf that allows golfers of varying abilities to enjoy themselves. I can't imagine playing the Old Course at St. Andrew's (and hopefully someday I will play it) without a caddy, given the undulations, bounces, pot bunkers and hidden hazards. I also can't imagine scoring as well as I did on the Blue course without our caddy. Links golf – be it on the Scottish coast or in the middle of Florida – benefits from somebody with knowledge of a course.

Likewise, a golf course is best traversed by foot, along the fairways rather than along the cart paths. Even though my dad and I took a cart, the beauty of the course should be evident in the photos I took, photos that only capture a fraction of what Doak, Coore and Crenshaw have created in one of the most unlikeliest of settings.

[Streamsong logo on a wall at the lodge]

This wraps up my three-part tour of Streamsong Resort. See also the first installment on the lodge and the second installment on the clubhouse. Head over to Flickr to see more photos of Streamsong.