OfficeUS Atlas edited by Eva Franch i Gilabert, Ana Miljački, Ashley Schafer, Michael Kubo

Storefront for Art and Architecture, Lars Müller Publishers, 2015

Hardcover, 1,250 pages

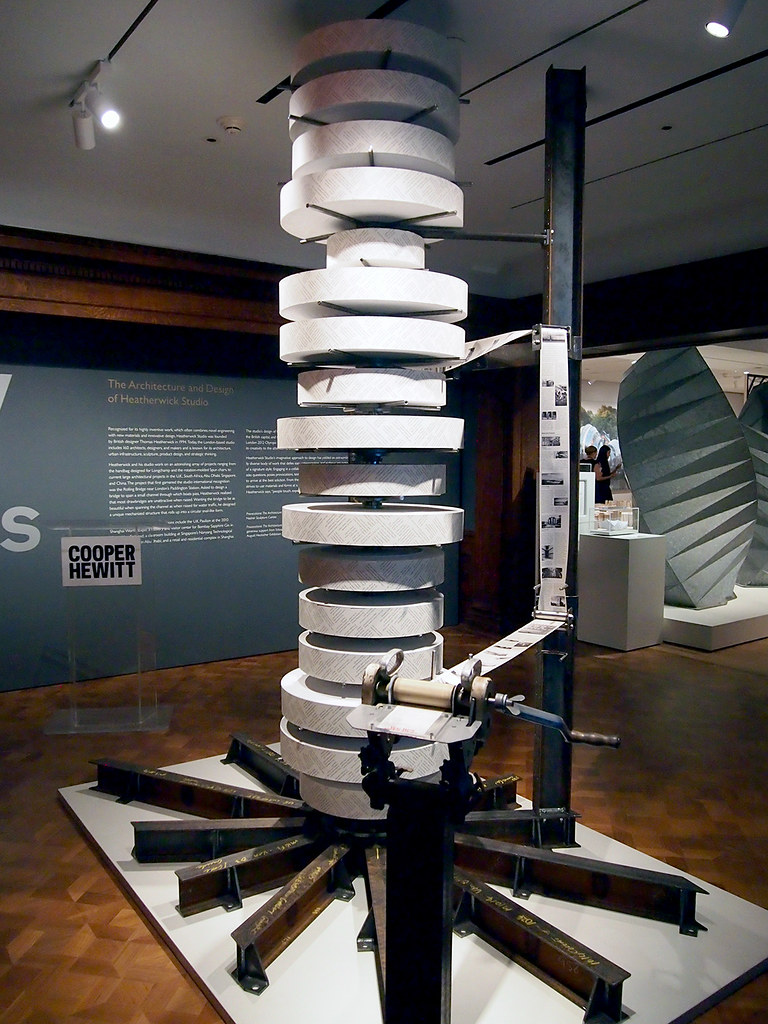

The 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale was one of the most anticipated since it started in the 1970s. Rem Koolhaas served as director and he aimed to unify the various national pavilions under one theme: "Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014." In most years the national pavilions do their own thing, often exhibiting the work of native architects; that is already the case with 2016 for the United States, which decided to focus on Detroit even before Alejandro Aravena was named director. But Koolhaas demanded more time and got it so he could leverage a bit more control and make the Biennale a bit more unified. For the most part it worked, with for the most part each country covering 100 years of architectural production. For the U.S. Pavilion, curated by Eva Franch i Gilabert, Ana Miljački, and Ashley Schafer, the theme was OfficeUS, which focused on American firms building overseas.

The U.S. Pavilion was the equivalent of information overload, since just about every wall of the "U"-shape building in the Giardini was covered with papers on American architects that the curators researched. These architects ranged from the obvious, like SOM and KPF, to smaller firms that would seem to be less likely to build overseas. But given the time frame covered in the exhibition, OfficeUS followed a number of changes in overseas, or imperial, architectural production. What was a rarity 100 years ago is now common practice, given the ease of telecommunications, travel and collaboration.

OfficeUS Atlas follows OfficeUS Agenda, which was published as a catalog to accompany the exhibition. It is much slimmer (only 272 pages) and more theoretical, since it "frames the narratives that have projected the organizational structures and branded identity of U.S. architecture firms internationally from 1914 - 2014." OfficeUS Atlas, on the other hand, is a gargantuan book on par with the exhibition itself. Thankfully it is not the book equivalent of the exhibition's information overload, since the design and layout help to break up the book into more manageable chunks and make it easy to navigate. The book works in a chronological order with content divided between archive materials (articles from magazines mainly) and profiles of firms building overseas; the former has pages with black edges and the latter has white pages, resulting in a book with black-and-white stripes. The order of the book makes the changing conditions of overseas work obvious, while it also (inadvertently?) shows how architectural publishing changed over the same period. Not only are some magazines long gone, but the content has changed from more big-picture and critical stories to project-specific coverage.

The combination of archive material and firm bios (with many projects illustrated with postage stamp-sized images) make this book appealing from different angles. Unfortunately, for those interested in the book as an archive the design falters. Although a black border is given around each clipped article (partially visible in the other two images above), there is no matching border in the fold. In many cases this does not affect the readability of the old articles (it should be noted these are smaller than their original page sizes, but they are still big enough to be read easily), but in far too many cases the text and/or drawings gets lost in the fold. Not allowing a margin in the fold is an inexcusable but common occurrence in architecture publishing. I've learned to overlook it at times, but I expect more from Lars Müller, who published this book and is known for thoughtful design in his books. Perhaps there was a sense on the part of the editors/curators that the archives were there for effect, to show how much and what has been written about the theme they developed. But far too often I found myself sucked into an old article only to turn the page and be frustrated by lost words – one blemish on an otherwise excellent book and record of an ambitious exhibition.

Storefront for Art and Architecture, Lars Müller Publishers, 2015

Hardcover, 1,250 pages

The 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale was one of the most anticipated since it started in the 1970s. Rem Koolhaas served as director and he aimed to unify the various national pavilions under one theme: "Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014." In most years the national pavilions do their own thing, often exhibiting the work of native architects; that is already the case with 2016 for the United States, which decided to focus on Detroit even before Alejandro Aravena was named director. But Koolhaas demanded more time and got it so he could leverage a bit more control and make the Biennale a bit more unified. For the most part it worked, with for the most part each country covering 100 years of architectural production. For the U.S. Pavilion, curated by Eva Franch i Gilabert, Ana Miljački, and Ashley Schafer, the theme was OfficeUS, which focused on American firms building overseas.

The U.S. Pavilion was the equivalent of information overload, since just about every wall of the "U"-shape building in the Giardini was covered with papers on American architects that the curators researched. These architects ranged from the obvious, like SOM and KPF, to smaller firms that would seem to be less likely to build overseas. But given the time frame covered in the exhibition, OfficeUS followed a number of changes in overseas, or imperial, architectural production. What was a rarity 100 years ago is now common practice, given the ease of telecommunications, travel and collaboration.

OfficeUS Atlas follows OfficeUS Agenda, which was published as a catalog to accompany the exhibition. It is much slimmer (only 272 pages) and more theoretical, since it "frames the narratives that have projected the organizational structures and branded identity of U.S. architecture firms internationally from 1914 - 2014." OfficeUS Atlas, on the other hand, is a gargantuan book on par with the exhibition itself. Thankfully it is not the book equivalent of the exhibition's information overload, since the design and layout help to break up the book into more manageable chunks and make it easy to navigate. The book works in a chronological order with content divided between archive materials (articles from magazines mainly) and profiles of firms building overseas; the former has pages with black edges and the latter has white pages, resulting in a book with black-and-white stripes. The order of the book makes the changing conditions of overseas work obvious, while it also (inadvertently?) shows how architectural publishing changed over the same period. Not only are some magazines long gone, but the content has changed from more big-picture and critical stories to project-specific coverage.

The combination of archive material and firm bios (with many projects illustrated with postage stamp-sized images) make this book appealing from different angles. Unfortunately, for those interested in the book as an archive the design falters. Although a black border is given around each clipped article (partially visible in the other two images above), there is no matching border in the fold. In many cases this does not affect the readability of the old articles (it should be noted these are smaller than their original page sizes, but they are still big enough to be read easily), but in far too many cases the text and/or drawings gets lost in the fold. Not allowing a margin in the fold is an inexcusable but common occurrence in architecture publishing. I've learned to overlook it at times, but I expect more from Lars Müller, who published this book and is known for thoughtful design in his books. Perhaps there was a sense on the part of the editors/curators that the archives were there for effect, to show how much and what has been written about the theme they developed. But far too often I found myself sucked into an old article only to turn the page and be frustrated by lost words – one blemish on an otherwise excellent book and record of an ambitious exhibition.