Venice Architectural Guide: Buildings and Projects After 1950 by Clemens F. Kusch and Anabel Gelhaar

DOM Publishers, 2014

Paperback, 280 pages

I've reviewed a number of architectural guides from Berlin's DOM Publishers (Japan, Taiwan, Pyongyang), but not until recently was I able to use one as properly designed – as a companion to traversing a city when in that city. Such is the case with Venice, when I took the publisher's latest book with me to the opening of Rem Koolhaas's much-anticipated Biennale. Before delving inside it's worth pointing out that, like DOM's other architectural guides, the book is tall and slender – hardly small but still portable, as it's not too thick, like certain guidebooks.

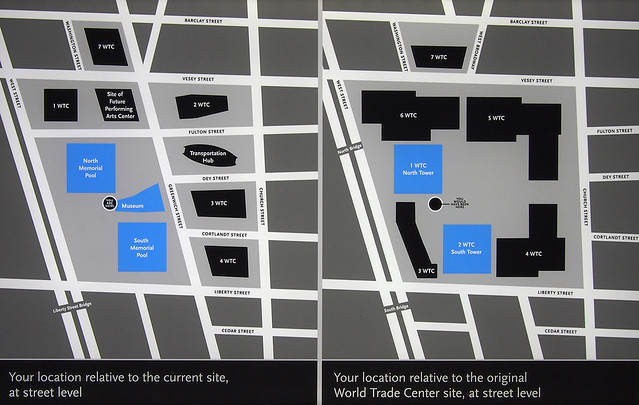

The book is organized into nine color-coded, geographical sections (well, actually eight are geographical, since the ninth is devoted to a "hypothetical Venice" that is scattered throughout the city) that are visible on a map in a fold-out behind the front cover. The back-cover fold-out includes a handy map of the Actv (water bus) network. At the start of each section are thorough maps (above) that locate the buildings in the guide but also recommended a route for seeing them. If any city is deserving of such routes it's Venice, where getting lost is the norm. (That said, there is value in leaving the guidebook in the hotel on some days so as to actually get lost and discover new things, one of the joys of being in Venice.)

One big difference between the Architectural Guide Venice and other DOM guides I've reviewed is the inclusion of aerial photographs (above) – lots of them. Each chapter has at least two or three, each with certain landmarks (not necessarily post-1950 projects in the guide) highlighted. These aerials do not function like the maps, aiding navigation through the maze that is Venice, but nevertheless they are helpful in understanding the extents of each section through their edges, be it the Grand Canal or the Guidecca Canal, for example. And of course it's just fun to look at the aerials to survey the mind-boggling complexity and beauty of Venice from above.

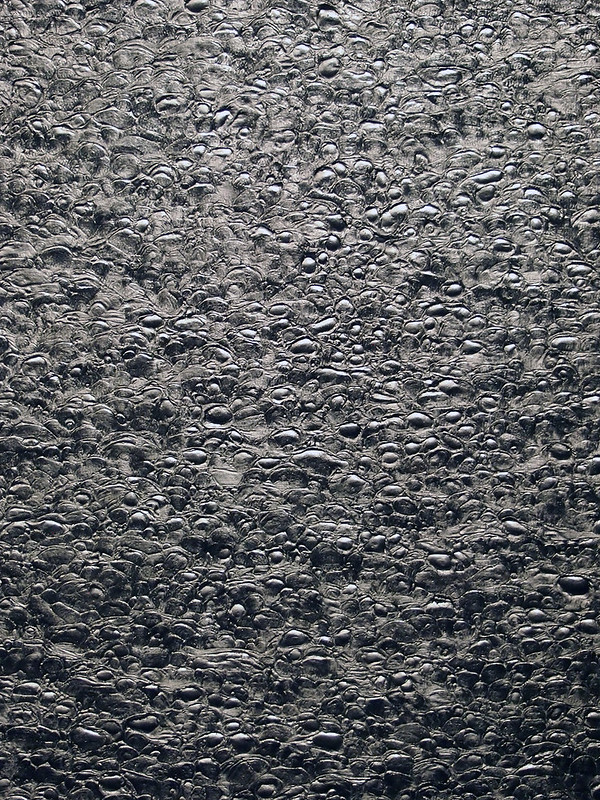

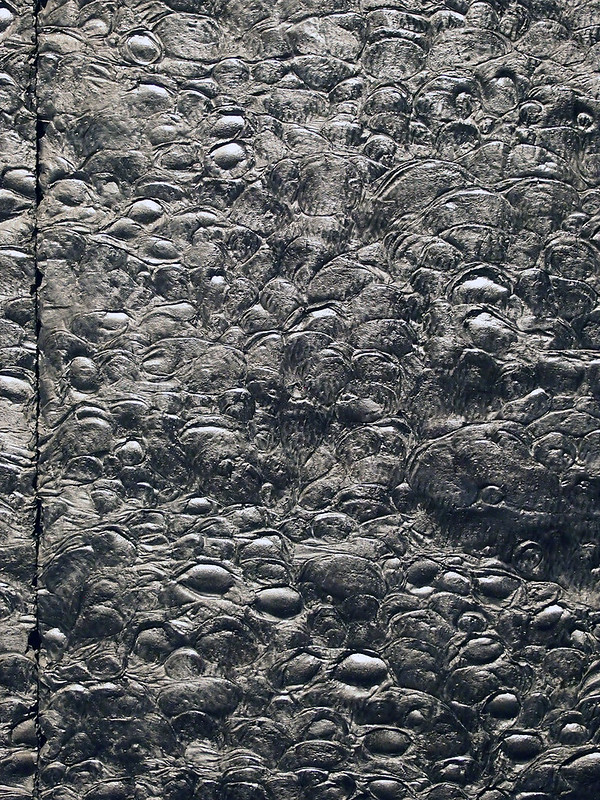

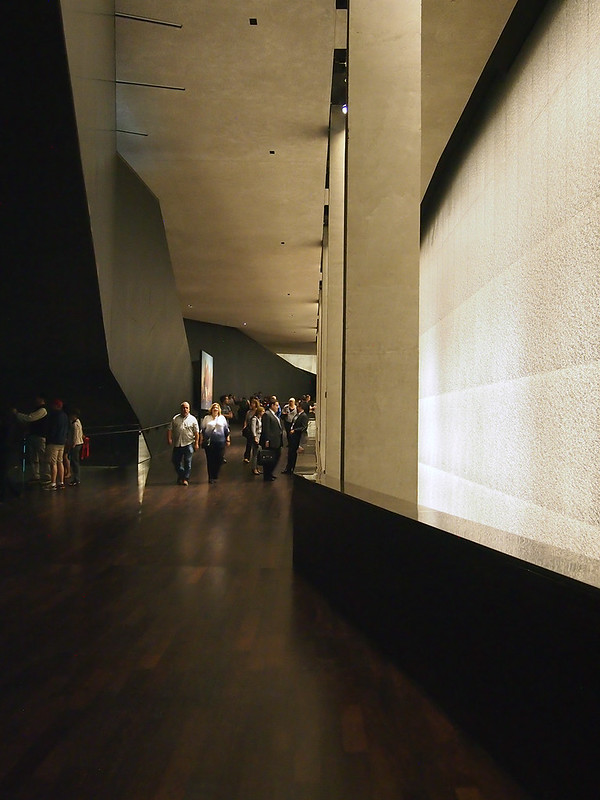

The authors acknowledge that there is a glut of guidebooks on Venice, but none of them to date have focused on architecture in the modern era. Doing so may seem like an odd choice in Venice, given that most of what is seen on a visit is old – turn a corner from one street lined with old buildings to another street and you'll find more old buildings. Regardless of this fact, there are plenty of post-1950 gems in the city, be it interior renovations (Carlo Scarpa's numerous projects and Tadao Ando's work for Palazzo Grassi (above) are two notable examples) or the many freestanding buildings in the Giardini (below) and the Guidecca, where Cino Zucchi has designed many apartment buildings.

The grounds of the Venice Biennale – the Giardini – are highlighted on yellow pages in chapter five, acknowledging the importance of this event (alternating art Biennales in odd years and architecture Biennales in even years, with cinema, dance, music, theatre interspersed throughou) in the cultural life of the city. A detailed map showing all of the national pavilions in the Giardini (even the ones done before WWII) is a helpful addition for those who visit, as I did on my first trip to this somewhat removed area, when the Biennale is not in session.

The ninth and last chapter, as mentioned, focuses on"hypothetical Venice." The other eight chapters include projects that are in progress, but this one shows us notable projects that never happened. The above spread highlights the unsuccessful attempts of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier to erect substantial edifices in the city. Their luck is echoed by architects today, who must venture to the mainland (Sauerbruch Hutton's M9) or another island (David Chipperfield's San Michele expansion) to do something more than interior renovations or small interventions.

All tolled, this is easily the best architectural guide that DOM has yet to publish, since it is so thorough in orienting the reader/visitor to the joys of Venice, be it the modern projects or its historical fabric. The best guidebooks are those that take into account how they will be used when "in location," and this one does it so well that it should be a model for other authors tackling other cities, be it for DOM or other publishers. Yes, much of the best qualities of the book arise from the specific circumstances of Venice, but the general approach and apparent joy the authors had in finding the best format for exploring the city are definitely worth exporting.

DOM Publishers, 2014

Paperback, 280 pages

I've reviewed a number of architectural guides from Berlin's DOM Publishers (Japan, Taiwan, Pyongyang), but not until recently was I able to use one as properly designed – as a companion to traversing a city when in that city. Such is the case with Venice, when I took the publisher's latest book with me to the opening of Rem Koolhaas's much-anticipated Biennale. Before delving inside it's worth pointing out that, like DOM's other architectural guides, the book is tall and slender – hardly small but still portable, as it's not too thick, like certain guidebooks.

The book is organized into nine color-coded, geographical sections (well, actually eight are geographical, since the ninth is devoted to a "hypothetical Venice" that is scattered throughout the city) that are visible on a map in a fold-out behind the front cover. The back-cover fold-out includes a handy map of the Actv (water bus) network. At the start of each section are thorough maps (above) that locate the buildings in the guide but also recommended a route for seeing them. If any city is deserving of such routes it's Venice, where getting lost is the norm. (That said, there is value in leaving the guidebook in the hotel on some days so as to actually get lost and discover new things, one of the joys of being in Venice.)

One big difference between the Architectural Guide Venice and other DOM guides I've reviewed is the inclusion of aerial photographs (above) – lots of them. Each chapter has at least two or three, each with certain landmarks (not necessarily post-1950 projects in the guide) highlighted. These aerials do not function like the maps, aiding navigation through the maze that is Venice, but nevertheless they are helpful in understanding the extents of each section through their edges, be it the Grand Canal or the Guidecca Canal, for example. And of course it's just fun to look at the aerials to survey the mind-boggling complexity and beauty of Venice from above.

The authors acknowledge that there is a glut of guidebooks on Venice, but none of them to date have focused on architecture in the modern era. Doing so may seem like an odd choice in Venice, given that most of what is seen on a visit is old – turn a corner from one street lined with old buildings to another street and you'll find more old buildings. Regardless of this fact, there are plenty of post-1950 gems in the city, be it interior renovations (Carlo Scarpa's numerous projects and Tadao Ando's work for Palazzo Grassi (above) are two notable examples) or the many freestanding buildings in the Giardini (below) and the Guidecca, where Cino Zucchi has designed many apartment buildings.

The grounds of the Venice Biennale – the Giardini – are highlighted on yellow pages in chapter five, acknowledging the importance of this event (alternating art Biennales in odd years and architecture Biennales in even years, with cinema, dance, music, theatre interspersed throughou) in the cultural life of the city. A detailed map showing all of the national pavilions in the Giardini (even the ones done before WWII) is a helpful addition for those who visit, as I did on my first trip to this somewhat removed area, when the Biennale is not in session.

The ninth and last chapter, as mentioned, focuses on"hypothetical Venice." The other eight chapters include projects that are in progress, but this one shows us notable projects that never happened. The above spread highlights the unsuccessful attempts of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier to erect substantial edifices in the city. Their luck is echoed by architects today, who must venture to the mainland (Sauerbruch Hutton's M9) or another island (David Chipperfield's San Michele expansion) to do something more than interior renovations or small interventions.

All tolled, this is easily the best architectural guide that DOM has yet to publish, since it is so thorough in orienting the reader/visitor to the joys of Venice, be it the modern projects or its historical fabric. The best guidebooks are those that take into account how they will be used when "in location," and this one does it so well that it should be a model for other authors tackling other cities, be it for DOM or other publishers. Yes, much of the best qualities of the book arise from the specific circumstances of Venice, but the general approach and apparent joy the authors had in finding the best format for exploring the city are definitely worth exporting.