A few days ago,

via Hyperallergic, I learned about the

Center for Innovation, Testing, and Evaluation (CITE), a $1 billion project proposed in 2011 by Pegasus Global Holdings "to be the largest scale testing and evaluation center in the world." Originally slated to be built in Lea County, New Mexico, the uninhabited 400-acre project was idle from 2012 until last year, when

news came out that Pegasus was going to restart the project for a site

"along Interstate 10 between Las Cruces and Deming." The architect responsible for the

master planning of CITE is Perkins + Will, which describes the project as "the transformation of a 22 square mile land holding in New Mexico into a serviced laboratory environment."

[All images, depicting the Lea County locale, are

courtesy of Perkins + Will, unless noted otherwise.]

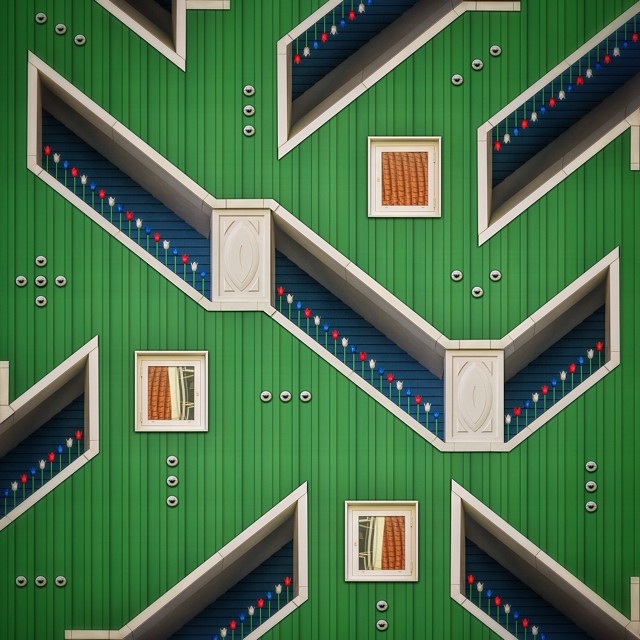

CITE is composed of

four main areas – City Lab, Field Lab District, Backbone, and Research Campus – but it's the City Lab that draws the most attention, since it is envisioned as "a representative example of a modern day, mid-sized American city ... [of 35,000 residents with] urban, suburban and rural zones as well as the corresponding infrastructure." Or as Hyperallergic puts it, the City Lab "will have a mall, airport, city hall, churches, power plant, highway, suburbs, townhouses, and downtown office buildings, but

no inhabitants" (my emphasis).

In being free of residents – seen as sources of "complication and safety issues," according to CITE – City Lab is reminiscent of places like the

Playas Training and Research Center, also in New Mexico. But instead of a strictly military

raison d'être, CITE is aimed at research and testing in four areas: Green Energy, Intelligent Transportation Systems (driver-less cars), Homeland Security, and Next Generation Wireless Infrastructure. CITE feeds into the notion that the world will be increasingly urbanized and technology is the key in making the city more sustainable.

[Image courtesy of CITE]

The above aerial rendering and below diagram clearly illustrate the various parts of City Lab, like a radial kit of parts taken from cities and suburbs, from a high-rise office building and interstate highway to a mock airport and a big box.

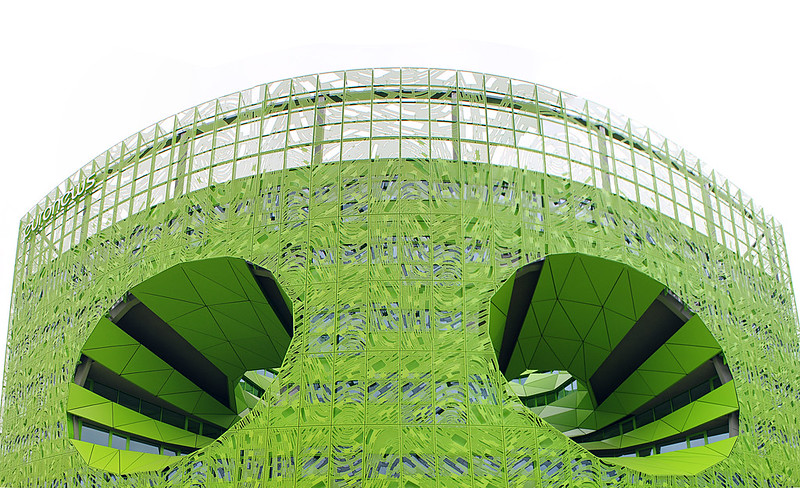

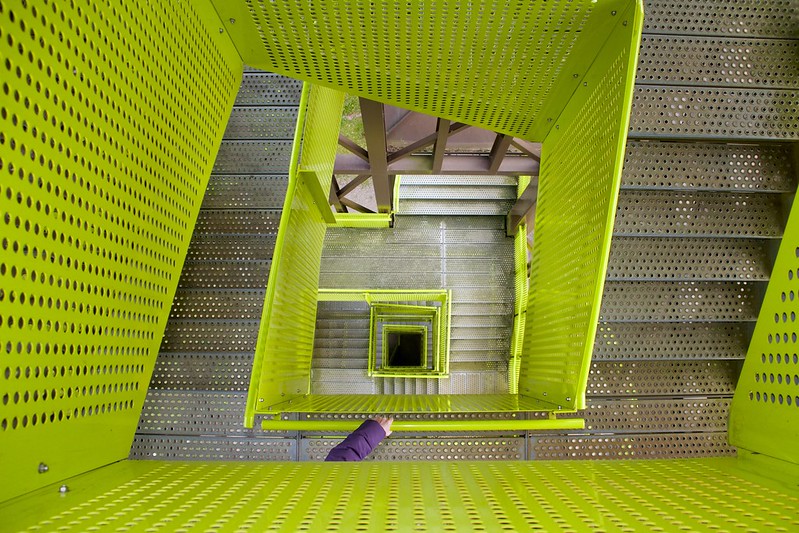

It's not surprising that the only capital-A architecture happens at the

CITE Campus (renderings below), located near CITE's entrance at a remove from City Lab, and operating "as the public outreach for CITE and as an independent economic development magnet for interested parties – researchers, universities, innovators and investors." Yet the CITE Campus, with its green roofs, solar panels, trellises, fountain and surface parking, is a capable yet unremarkable design that is part of a project that borders on science fiction or fantasy. Perhaps this conservative design makes sense, given that the City Lab for 35,000 invisible residents will be chockablock of mundane buildings – if it ever gets built.