AIA Guide to Chicago edited by Alice Sinkevitch and Laurie McGovern Petersen

University of Illinois Press, 2014, Third Edition

Paperback, 568 pages

Building Ideas: An Architectural Guide to the University of Chicago by Jay Pridmore

University of Chicago Press, 2013

Paperback, 160 pages

Chicagoisms: The City as Catalyst for Architectural Speculation edited by Alexander Eisenschmidt with Jonathan Mekinda

Park Books, 2013

Hardcover, 184 pages

Recently I received review copies of three books on Chicago, so it seems appropriate to put them together into one review, discussed in alphabetical order.

Recently I received review copies of three books on Chicago, so it seems appropriate to put them together into one review, discussed in alphabetical order.Having produced

my own guide to architecture in New York City, and therefore having researched many guidebooks, one of my pet peeves with guidebooks (architectural or otherwise) is when they are not designed with their use in mind. By this I mean being carried around, having easy-to-find entries and easy-to-navigate maps, and giving the reader something of interest while seeing the site in person. Although the

AIA Guide to Chicago excels in many respects (to be discussed soon), the third edition actually takes a step back from the 2004 edition in one important area: maps. The new edition forgets one thing the previous edition was aware of: books have folds where information gets lost, so don't put anything within about 1/4" or 1/2" of the fold. Unfortunately the maps don't heed this advice, so many streets and buildings in the two-page maps are lost, only to be found by those that break the binding or cut the book apart. This is unfortunate, more a mistake for a first edition than a third, especially when the second edition got it right.

With that out of the way, the positive aspects of the guidebook are many, building upon the previous edition (also edited by Sinkevitch) with better navigation (page-end tabs make the chapters easy to find), thorough histories of the city and neighborhoods, commendable fact-checking (unlike the

AIA Guide to New York, as

I wrote in my review), and good additions with the many contemporary buildings that are once again making Chicago an exciting place to be an architect and archi-tourist. Things were not so optimistic when the previous edition came out in 2004, timed, like the third edition, to the AIA Convention descending on the city.

I'll admit that in the decade I worked as an architect in Chicago (1997-2006), there was a general malaise with architects in the city, brought on by important projects going to outsiders and bland buildings being erected by locals (Millennium Park was just completed in 2004, so its impact was not yet felt). There were bright spots with Jeanne Gang, John Ronan, Wheeler Kearns, and Brininstool + Lynch, among others, but mediocrity was the norm over the design excellence Chicago is known for, rose-colored glasses or not. But positive momentum has been in swing as Gang, Ronan (below photo) and others have received more commissions and created some of the best architecture in the city, with buildings that are drawing attention to far-flung parts of the globe – Gang's Aqua Tower, the most obvious expression of this, graces the cover for good reason. Of course, there is much more to see than Aqua, and this book (warts and all) is a good companion to exploring the city from what's left of its 19th-century origins to the present.

[Poetry Foundation, John Ronan Architects, 2011 | Photo by John Hill]

When a review copy of

Building Ideas: An Architectural Guide to the University of Chicago landed on my doorstep, the first thing my wife asked was, "what do they say about the Smart Museum?" where we got married in 2006. Turns out the answer was "nothing." I could find the museum labeled #2 on a map near the front of the book, but when I flipped through the book to find the same, thinking it might be arranged in order of the 31 buildings on the map, I couldn't find it. The chapters are chronological/thematic, moving from "The Gothic Campus" to "Building Ideas with Modern Architecture," so projects are out of sync with the numbering on the map. OK. But looking in the index, the only mention of the Smart Museum of Art is for the two-page spread of the map. I checked the 30 other buildings and discovered only one other building (International House) in the same predicament; every other building is discussed at some length in the book.

So what does the inclusion of the Smart Museum in the map but its omission from any description say about the book? First, combined with the somewhat large size of the book (10"x9"), it's not an "architectural guide" in the sense of the

AIA Guide to Chicago or any other portable, keyed-and-mapped guidebook. A more accurate subtitle would have been "an architectural history of the University of Chicago," given the way the chapters are arranged, the narrative flow of Pridmore's writing, and the way the reader learns about the planning and evolution of the physical campus. Most people will not notice the omission of the Smart Museum from the text, but if they used it as a guide to the campus, as the subtitle indicates, they most certainly would have noticed. (That said, Pridmore did produce

an architectural tour of the campus in 2006 as part of PAPress's campus guide series, a more traditional guide that predates the university's latest building boom.)

Aside from the quibble of "guide" versus "history," how is the book? While it does a great job in describing the evolution of the campus from its origins, selection of architect/planner, and even selection of style (less obvious and more important in the late 1800s than today) to its modern plans by Eero Saarinen and Edward Larrabee Barnes (he was architect of the Smart Museum, but in the book's one mention of the museum – not by name – it and other Barnes-era buildings "did not meet expectations") and the latest boom with buildings by Helmut Jahn, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, and Valerio Dewalt Train. But when it comes to the overall tone of the book and descriptions of the individual buildings, the book is more "booster" than either history or guide, as if the book is a promotion for the school rather than a scholarly or independent voice on it. Regardless of the Smart Museum's omission, people like me, with a fondness for the school in their hearts (this goes for alumni, professors and others who have spent time there for whatever reason), will find the book rewarding, but those looking for a proper guide should go with the

AIA Guide, which devotes nearly 20 pages to more than 80 buildings on its Hyde Park campus.

[

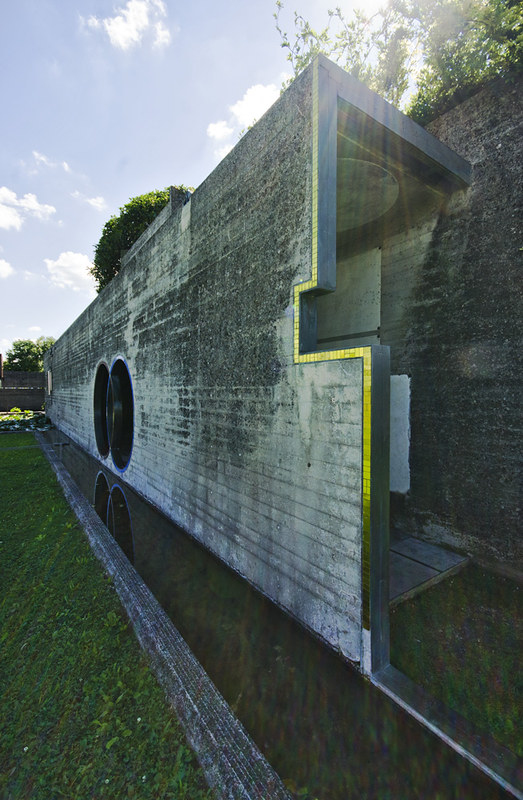

Chicagoisms exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago | Photo by John Hill]

Chicago is a city whose mythologies are more prevalent to foreigners than other cities. In my travels in Europe in the mid-1990s, just about everybody I met and told I came from Chicago replied with something about Al Capone and the mob ("stick 'em up, bang, bang!), or personalities like Oprah Winfrey and Michael Jordan, or its great architecture being limited to Frank Lloyd Wright and the "birth of the skyscraper." Even today, people tell me that it makes sense I'm an architect/architectural writer, considering I came from the city. People's impressions of Chicago are colored by personalities whose contributions were great but which overshadow the complexities and realities of the city. Many histories repeat these myths and simplifications, but this great book thankfully goes the opposite route, dismantling some of those myths and putting Chicago in an international context that shines a light on its influences.

The dismantling of myths starts right away with the first essay (of eight), Penelope Dean's comparison of two contemporaneous exhibitions in 1976:

100 Years of Architecture in Chicago: Continuity of Structure and Form and

Chicago Architects. The first, organized by SOM's Peter Pran and Mies biographer Franz Schulze, was representative of the myth (still strong) that painted Chicago architecture as starting with the Chicago School, moving through Mies, and then culminating (at the time) with corporate modern firms like SOM. The second, on the other hand, argued that such a simple view was misleading, ignorant of the variety in Chicago architecture that was portrayed in the show; Stanley Tigerman and Stuart Cohen, among others, were responsible for the oppositional exhibition. Dean's analysis examines the two exhibitions but also how people in places like New York reacted to the shows and how they viewed architecture in Chicago.

The following essays take further in-depth, scholarly looks at Alvin Boyarsky, the Museum of Modern Art's 1933 exhibition on Chicago, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Burnham's Plan of Chicago, and of course Mies van der Rohe, among other subjects. Each one ties Chicago to another Place (London, New York, Berlin, etc.) as a means of lending alternative viewpoints to the city as, among other things, a testbed for innovations in architecture and urban design. Aiding the essays are 20 short-form pieces (each one a two-page spread on a pink background) that focus on a particular project from an atypical perspective (buildings by Mies, Bertrand Goldberg, and SOM, as well as projects by the likes of Greg Lynn, Sean Lally, and others). All tolled, the book is one of the freshest recent books on architecture in Chicago, one that inspired the Art Institute exhibition of the same name, in which some voices from the book use the essays as frameworks for speculating on Chicago's future evolution. Perhaps a future edition will combined the book and the exhibition to make an even better document of Chicago's realities and potential realities.