[

Conflict Space, 2006 – All photos of the exhibition at The Drawing Center by John Hill.]

There is something appealing about cycles, about the sun rising and setting, the changing of the seasons, the earth rotating about its axis as it revolves around the sun, even the way some of the best narratives seem to come full circle on themselves. The life of

Lebbeus Woods (1940-2012) is a remarkable cyclical composition when seen relative to the oldest and most recent pieces in the exhibition

Lebbeus Woods, Architect, opening today at The Drawing Center in SoHo. First is

Einstein Tomb, which was published as

Pamphlet Architecture #6 (the long out-of-print title is available at The Drawing Center as part of the exhibition) in 1980.

[

Einstein Tomb, 1980]

Through words and drawings Woods speaks in

PA#6 about Einstein's world-changing view of the universe as "a warp of finite duration and boundary yet of infinite renewal and continuity." Woods finds the circle to be the form of the Eisensteinian universe, as it "creates the epicycles of day, month, year, and millennium," while also tapping into the mystical realm of Cabala. Through this view Woods designs a tomb whose form "has always been known" and which we can envision spinning infinitely about its axis. Woods describes the tomb as "a vessel journeying outward on a beam of light," as poetic an epitaph as can be imagined.

[

Einstein Tomb, 1980]

[

Einstein Tomb, 1980]

PA#6 was published in 1980 with Steven Holl, whom Woods met some years before and pitched the idea for the project while at a diner not far from The Drawing Center, in the downtown neighborhood where Woods lived. Thirty years after

Einstein Tomb, Woods and Holl collaborated (with Christoph a. Kumpusch) on what would become Woods's last major project and his only full-scale, permanent work:

The Light Pavilion.

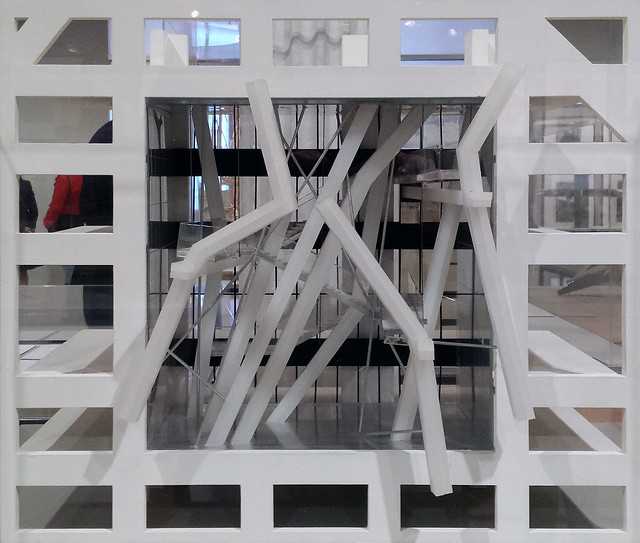

[

Light Pavilion, 2011]

The pavilion is set into a four-story-high space carved from Holl's huge

Sliced Porosity Block project in Chengdu, China. Three decades after Einstein Tomb, it's clear that Woods was still infatuated with science, especially the notion of "a beam of light." The piece appears to capture the moment of light/energy's creation, solidifying it in glass, polycarbonate, and steel. So from 1980 to 2011 in these two projects, Woods's life came full circle through the preoccupations of its creator, his collaborations, and the stories he endeavored to tell through drawings, models, writings, exhibitions, teaching, and lecturing.

It's important to point out the various media (drawings, models, words, etc.) through which Woods explored his designs, for while he is known primarily as an illustrator that label is limiting. It is telling that curators Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher chose the title

Lebbeus Woods, Architect – rather than, say,

Lebbeus Woods, Illustrator – for the exhibition that started at SFMOMA and traveled to the Broad Art Museum before arriving in Woods's home city.

Woods may not have realized buildings like others called "architect," but he explored the shaping of form, space, and light through drawings, models and words, as well as through his work in academia, just like other architects. He did not just draw amazing pictures (though he was often paid early in his career

to do just that); he imagined worlds that arose from life-changing ideas in science and philosophy, from the destruction of natural disaster and warfare, and generally from the conditions of the modern world where other architects dared not tread.

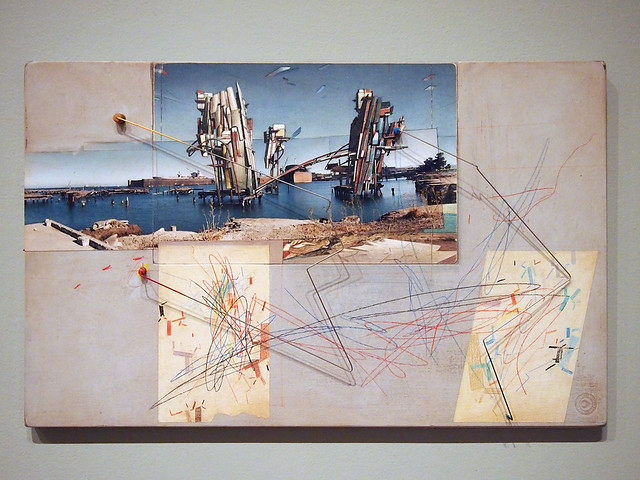

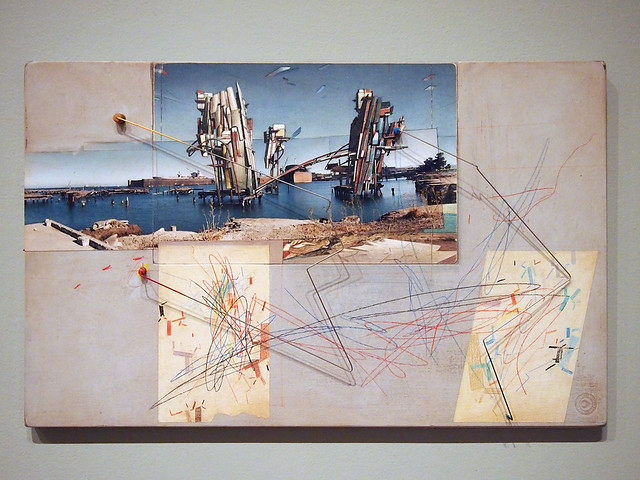

[

High Houses and

Sarajevo, from

War and Architecture, 1993]

According to The Drawing Center, "Woods worked cyclically, returning often to themes of architecture's ability to transform, resist, and free the collective and the individual." Therefore it makes sens that the curators "provide a thematic, rather than chronological, framework for understanding the experimental and timeless nature of Woods's work." Clusters of drawings like those above and below illustrate how these themes and projects are experienced in the exhibition.

[

San Francisco: Inhabiting the Quake, 1995]

[

Shard House, from

San Francisco: Inhabiting the Quake, 1995]

A cyclical reading of Woods's career makes sense, given his consistently sure hand and distinctive form-making. He applied the themes and lessons of each project to others like a feedback loop rather than in a linear fashion; or at least that's the sense I get from absorbing his drawings and the models he developed with his collaborators. The projects he worked on during the immensely productive three decades from around 1980 until his death (before that he worked for Eero Saarinen and Kevin Roche in the 1960s and had a private practice in the 1970s) are akin to the epicycles of the Einsteinian universe.

[

Zagreb Free Zone, 1991]

[

Zagreb Free Zone, 1991]

That the third and final leg of

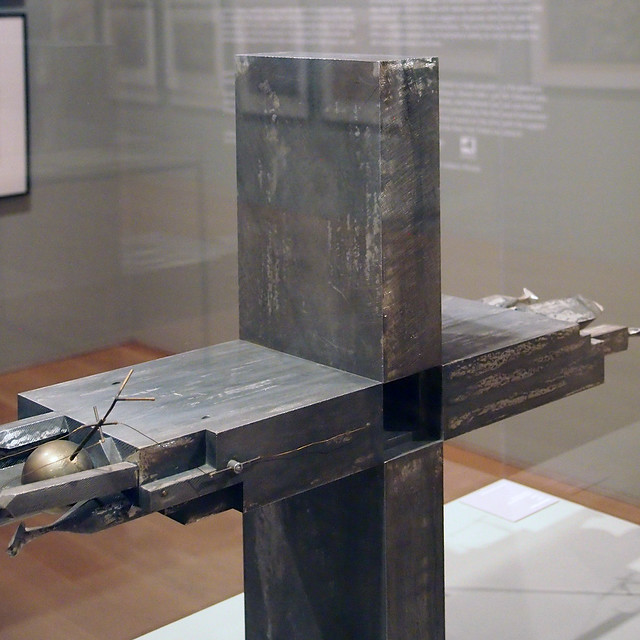

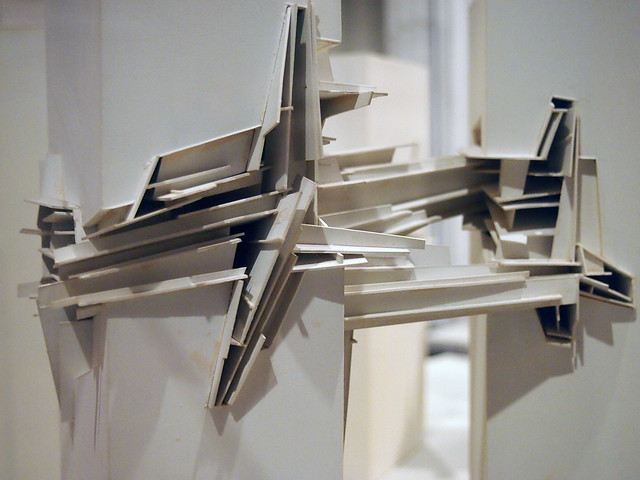

Lebbeus Woods, Architect is at The Drawing Center makes total sense, not only because Woods lived in New York City, but because the institution focuses on that overlooked media of art: drawing. Yet even though Woods is easily one of the best architectural delineators of the last 100 years, as mentioned earlier he did not draw at the expense of explorations in other media. It's then worth highlighting the models he built with talented model builders, each given credit in the exhibition, whose central area by the cast-iron columns is loaded with models in vitrines.

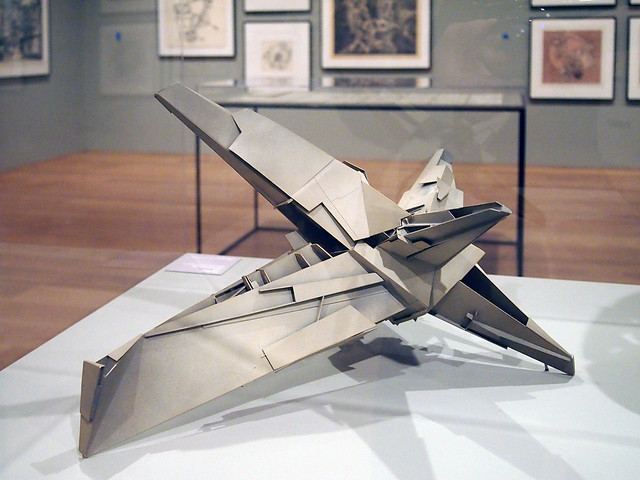

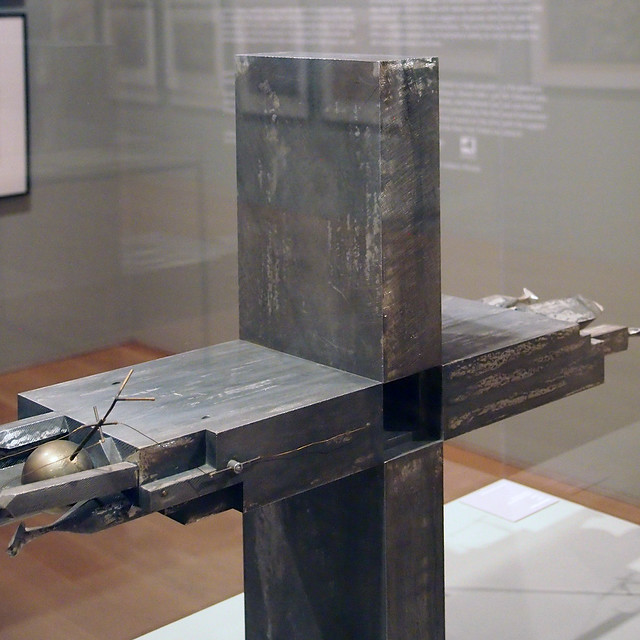

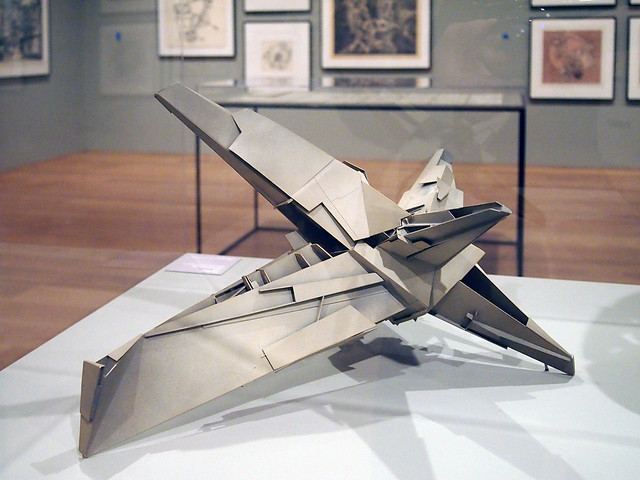

[

Nine Reconstructed Boxes, 1999]

[

Nine Reconstructed Boxes, 1999]

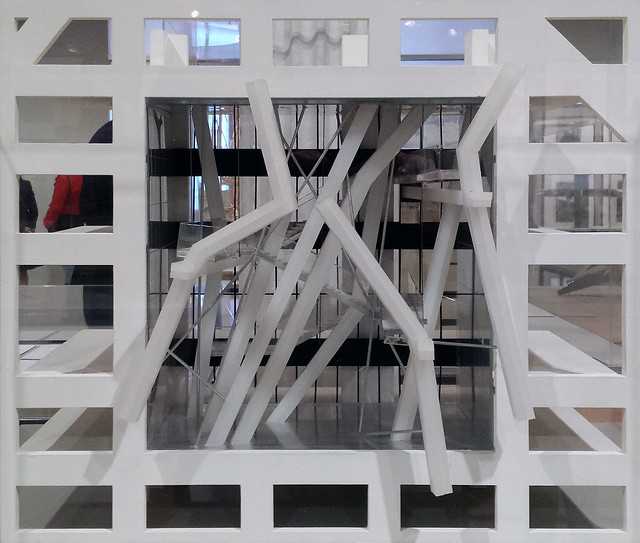

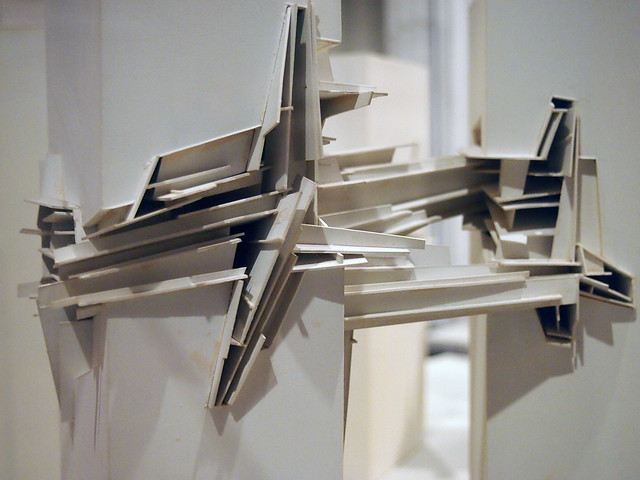

In particular I'm amazed by the model

Terrain that Woods built with Dwayne Oyler, an old classmate of mine and one-half of

Oyler Wu Collaborative. The valise-like model, which is

now in the MoMA collection, is located in a prominent location near the front door of The Drawing Center. At the opening reception last night, I noticed many people immediately drawn to the model rather than the large drawings or introductory text on the nearby walls.

[

Terrain, 1999]

[

Terrain, 1999]

I recall visiting NYC in the late 1990s with some fellow classmates and seeing the model in progress in Dwayne's tiny SoHo apartment. The skill and patience infused in such a complex design is obvious, but it and other models and makers should be commended for being able to turn Woods's 2-D drawings into 3-D models – no easy feats, but I'd wager eminently rewarding ones.

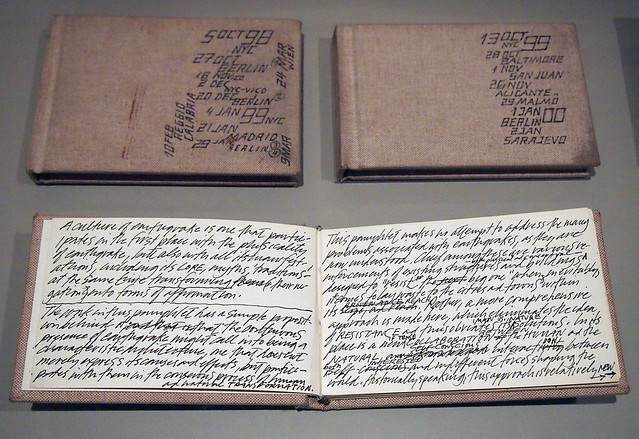

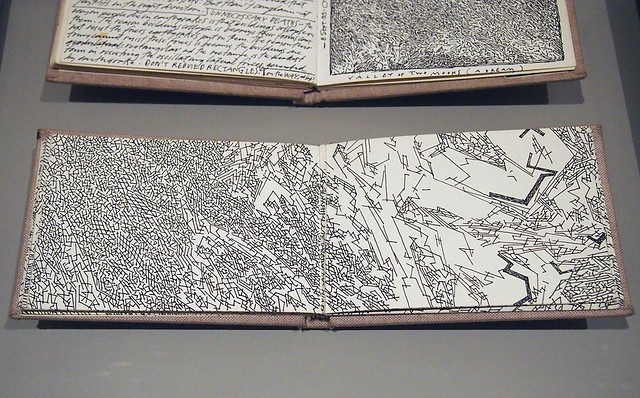

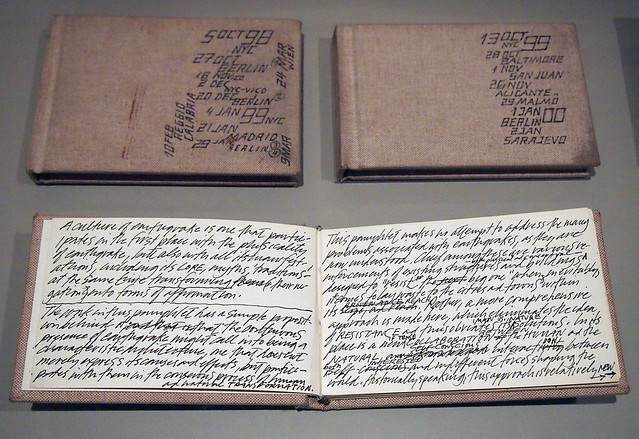

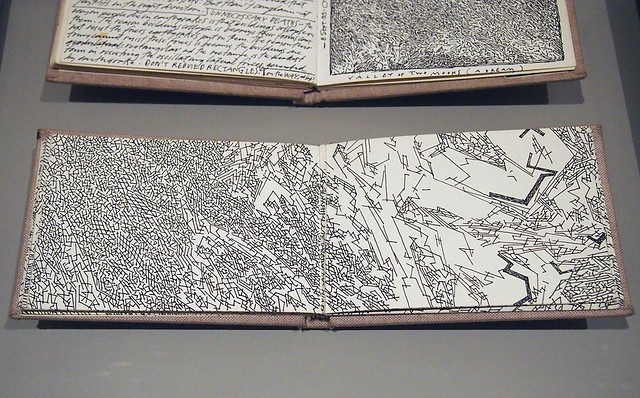

[

Star House, 1996]

A third aspect of the exhibition – in addition to the illustrations and models – are the in-progress drawings found in the sketchbooks that recorded Woods's thoughts and doodles. On display under glass in vitrines, the first thing one notices is the consistent format of the sketchbooks, something again in common with Steven Holl, whose well-known watercolors are organized methodically in his office. Woods favored a small, landscape-oriented sketchbook with a linen cover, but as can be seen he often ignored the fold and let drawings extend from one page to the next.

[

Sketchbooks, 1999-2000]

[

Sketchbooks, 1999-2000]

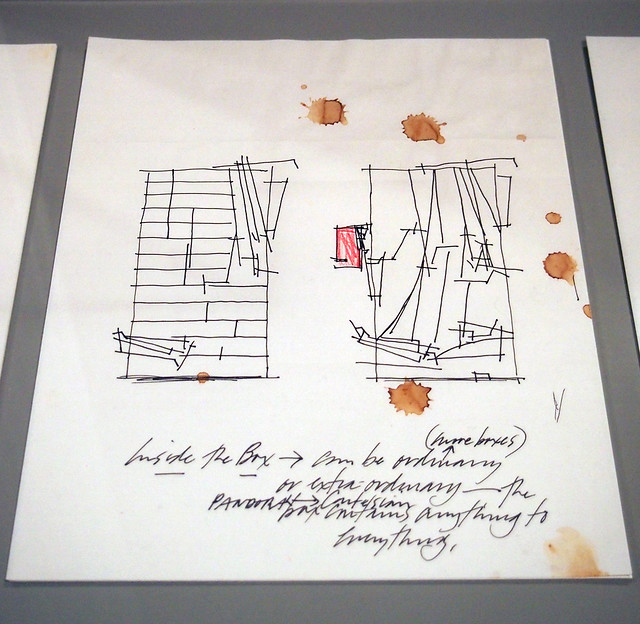

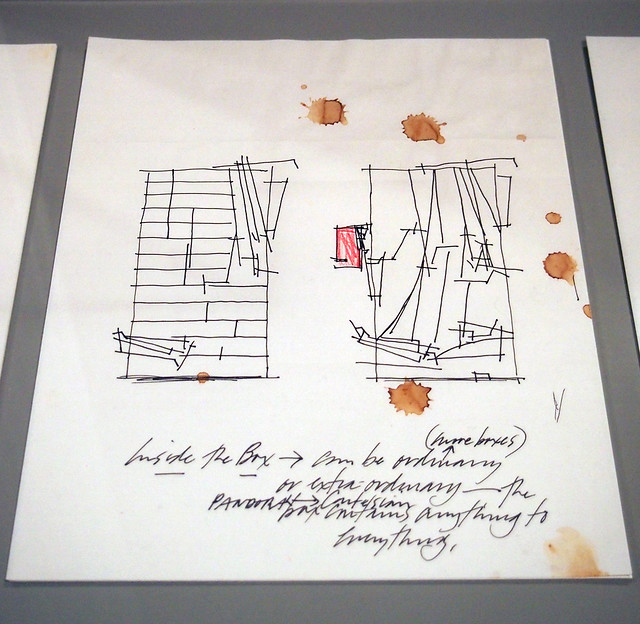

This last photo, a sketch from

Nine Reconstructed Boxes, is one of the oddest pieces in the exhibition, for the polish of Woods's final drawings and even his sketchbooks is marred by some coffee stains. Yes, every drawing and model respectively exhibits the hands of Woods and his collaborators, but this sketch reveals the accident, the all-too-human occurrence that has happened to all of us at one time or another. More important than the fact the spill happened is the fact it remains, that the sketch was not thrown away and started over on clean paper.

[Sketch from

Nine Reconstructed Boxes, 1999]

Yet we can find in these coffee stains as much about what Woods devoted his life to as in the ink of his imagined places. For his designs were ultimately about freedom and humanity in the face of, per the curators, "contemporary political, social, and ideological conditions, and how one person contributes to the development and mutation of the built world." His contribution is felt all the more strongly as we imagine Woods over his paper with pen in one hand and coffee in the other.

.jpg)

.jpg)