[All photographs by John Hill – see more in my Flickr set on the exhibition.]

[All photographs by John Hill – see more in my Flickr set on the exhibition.]Earlier in the week I got a preview of the MoMA exhibition

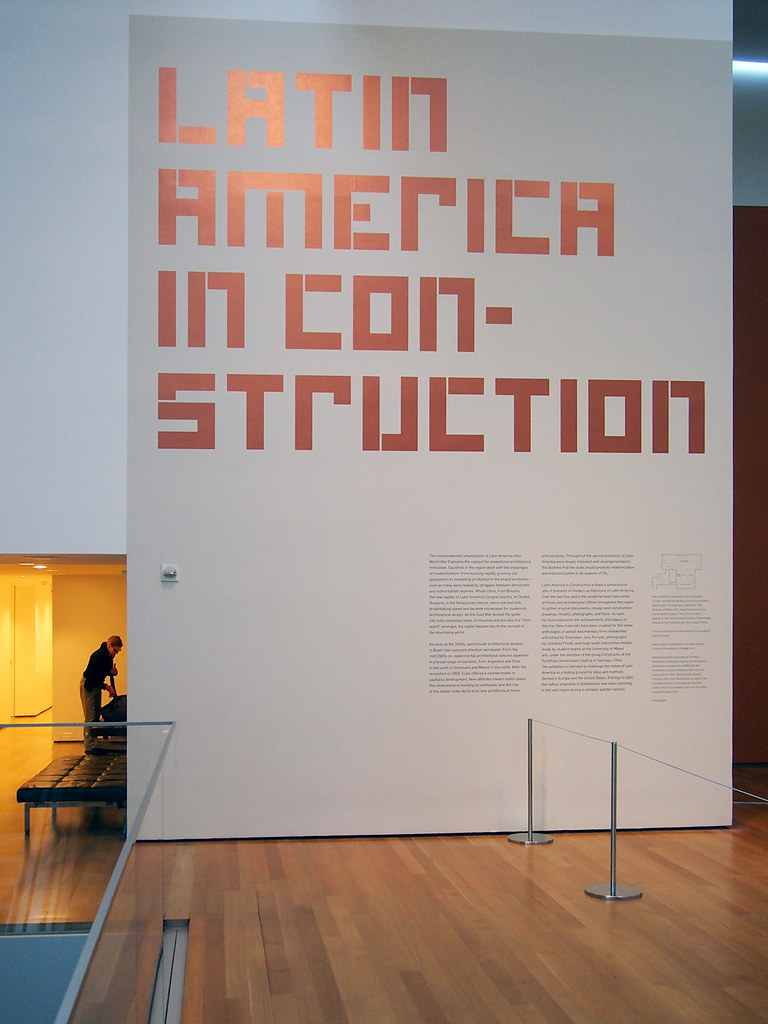

Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980, opening Sunday and running until July 19, 2015. The large-scale show, located on the museum's sixth floor (where

Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes took place two years ago), is notable for being Barry Bergdoll's swan song at MoMA, although he organized the show with a number of people: Patricio del Real, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art; Jorge Francisco Liernur, Universidad Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina; and Carlos Eduardo Comas, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; as well as an advisory committee from across Latin America.

The show is also notable for being the first time MoMA has devoted a single exhibition to Latin American architecture since 1955, when it staged

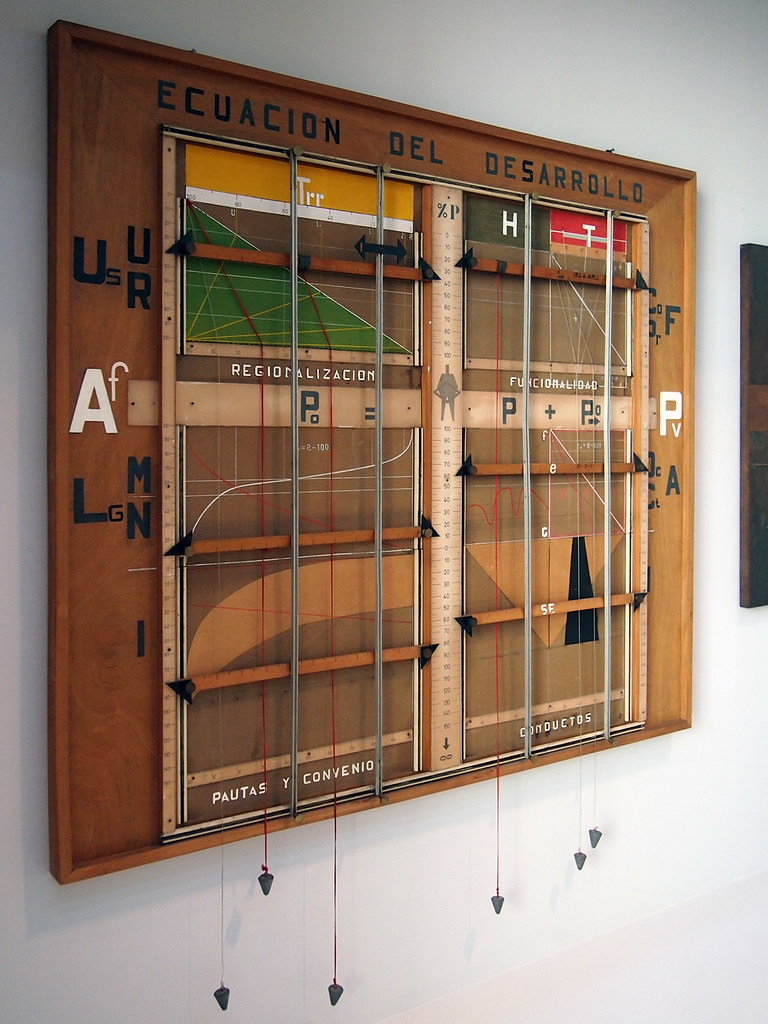

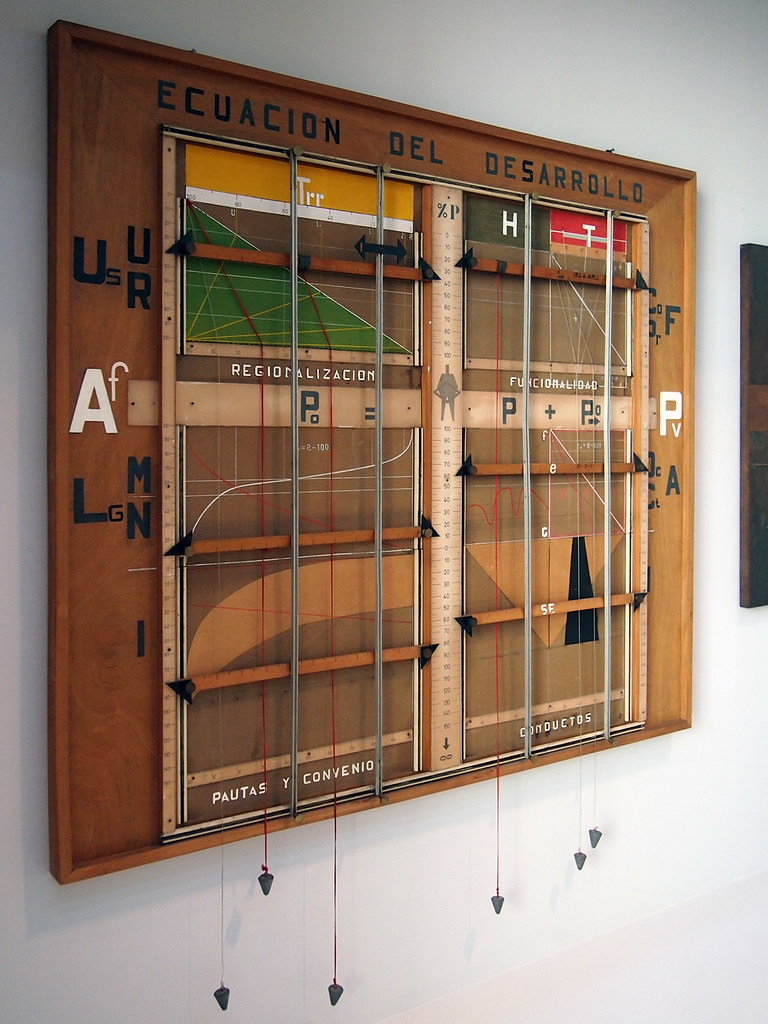

Latin American Architecture since 1945, "a landmark survey of modern architecture in Latin America." But where that show focused on contemporary architecture, this one is historical, looking back to 25 years of architectural production, from the year of that exhibition to the early days of Postmodernism and the Thatcher/Reagan years. In MoMA's words, Latin America saw in these years, "self-questioning, exploration, and complex political shifts [and] the emergence of the notion of Latin America as a landscape of development, one in which all aspects of cultural life were colored in one way or another by this new attitude to what emerged as the 'Third World.'" This embrace of politics, economics and planning, in addition to some amazing architecture, is evident in an elaborate model depicting the "Development Equation" that is hung on a wall outside the entrance to the exhibition:

[At the entrance to the exhibition is the "Development Equation" (1960) by Carlos Gomez Gavazzo.]

[At the entrance to the exhibition is the "Development Equation" (1960) by Carlos Gomez Gavazzo.]Stepping inside the exhibition through the sliding glass doors, the museum goer is confronted by a partly darkened room with video screens and overlapping sounds, the exhibition's "prelude." A map of South and Central America is visible on the floor, moving from south to north. Bergdoll, in remarks to the press on Tuesday, referred to this map as "corrected," as it is not seen from the perspective of a visitor from the northern hemisphere. The relationship of the north to the south is an important one, since it establishes that, even with the help of his fellow curators, Bergdoll is looking from the outside in, making up for what he described as an education, three degrees and all, that was deficient in learning about Latin American architecture. It also defines limitations on the projects included in the exhibition, the main one being that buildings designed by European, North American and other outsider architects for the region are not included; the focus is on architects working locally and, in the very last part of the show, their ideas and work being exported to other continents.

The seven videos forming a curve in one corner of the room are one of the exhibition's many pieces I need to return to (the whole show is too much to take in during a short press preview). While only 8-1/2 minutes long, the brief visit on Tuesday did not allow enough time to absorb what these films filled with archival materials are trying to say about each city, country and the region as a whole. Suffice to say, Forsyte's editing produces overlaps at times, visually illustrating the overlap that often occurs between the various Latin American countries.

[The first room of the exhibition includes seven screens with city portraits created by Joey Forsyte and consisting of archive materias on Buenos Aires, Montevideo, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Caracas, Havana, and Mexico City.]

[The first room of the exhibition includes seven screens with city portraits created by Joey Forsyte and consisting of archive materias on Buenos Aires, Montevideo, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Caracas, Havana, and Mexico City.]After the prelude, the exhibition moves into a section on "Campuses," focusing on planning projects, particularly university cities. Logically the next gallery is devoted to Brasilia, which is documented with original, browning plans by Lucio Costa, drawings by Oscar Niemeyer, models and photographs:

[Construction photographs of Brasilia by Marcel Andre Felix Gautherot.]

[Construction photographs of Brasilia by Marcel Andre Felix Gautherot.] [Brasilia room, with the bulk of the exhibition lying beyond the opening.]

[Brasilia room, with the bulk of the exhibition lying beyond the opening.]But the galleries on Campuses and Brasilia give just a taste of the exhibition, which opens into a large space with flowing galleries and walls left open on the top, like a metaphor of the words "in construction" in the exhibition's title. Here are a handful of general views of the exhibition, which is comprised mainly of two parts: "Latin American in Development: 1955-1980" and "A Quarter Century of Housing," the former interspersed among the gray walls and the latter covering the long yellow wall:

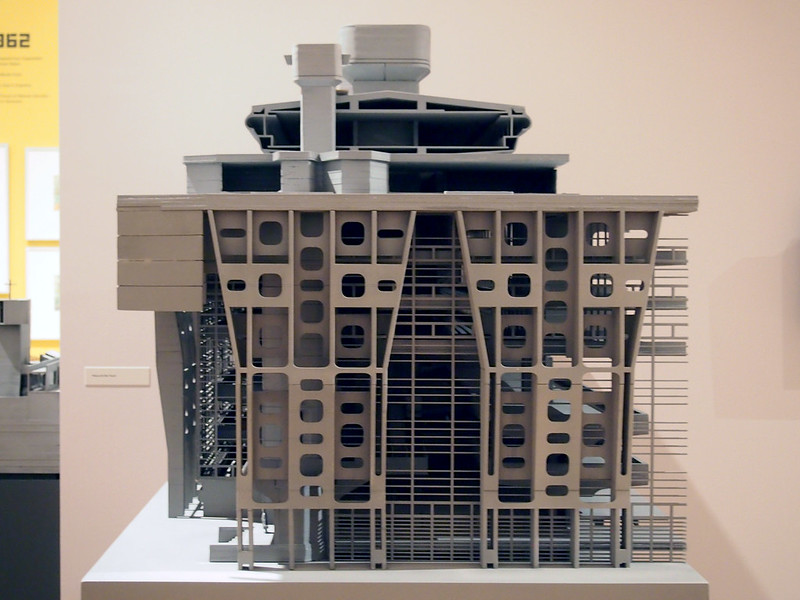

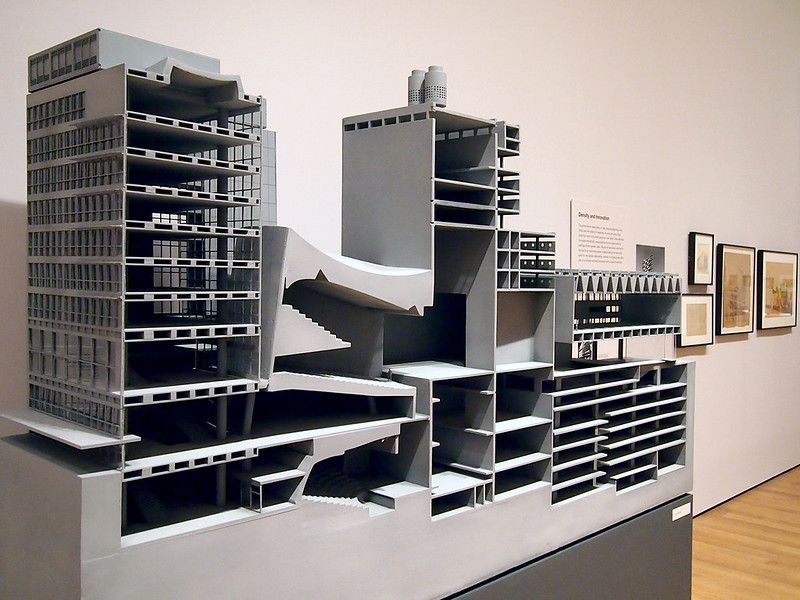

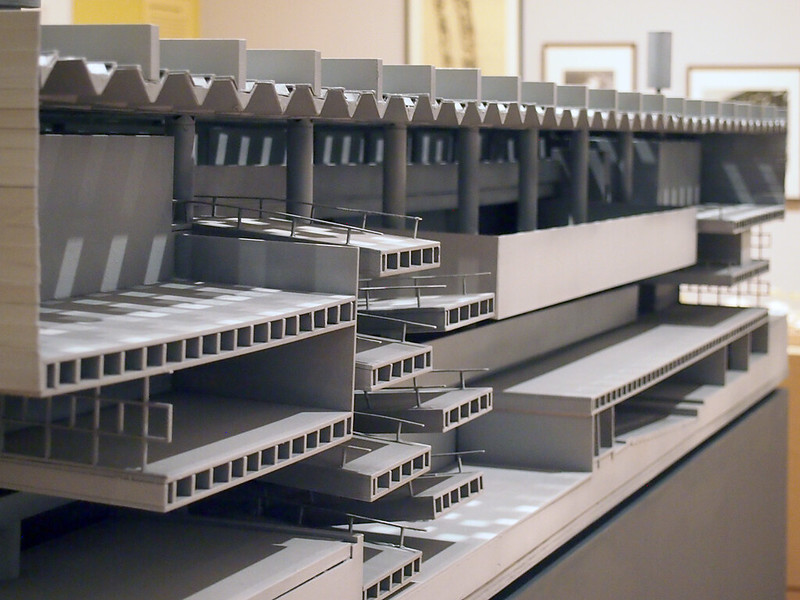

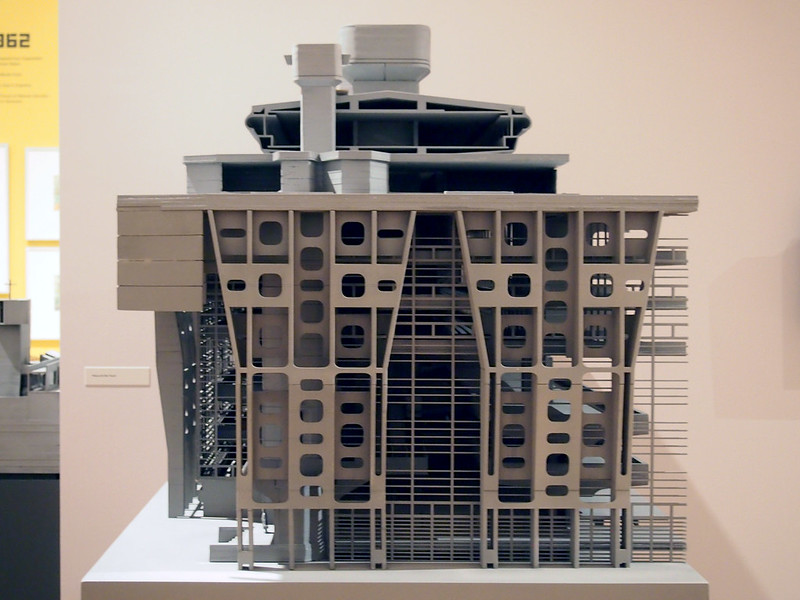

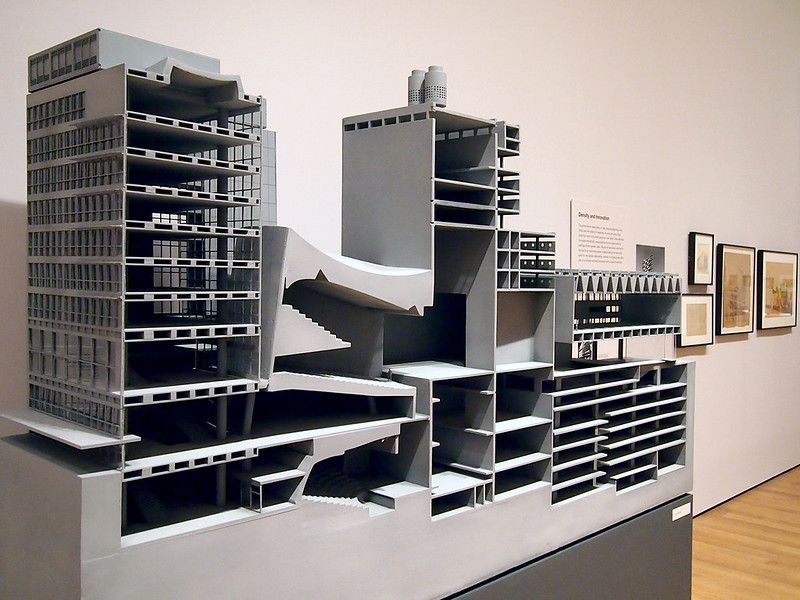

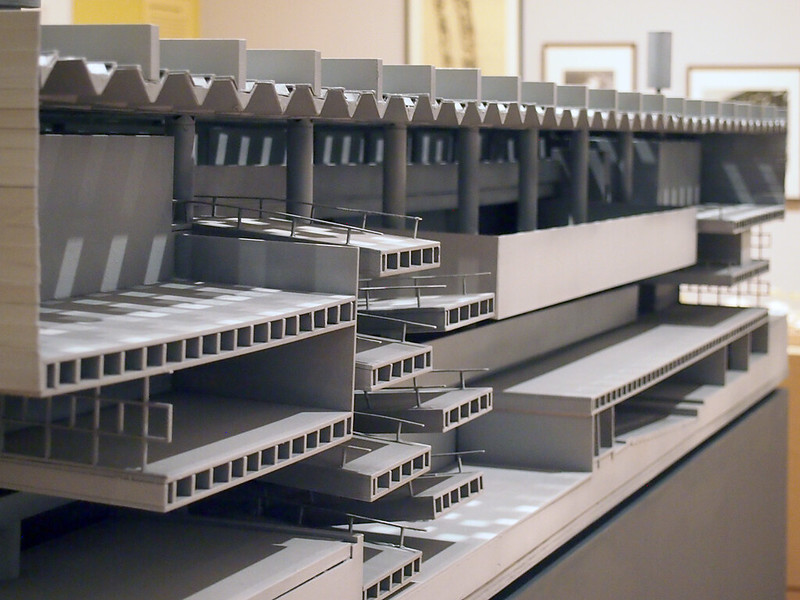

The various projects highlighted in the exhibition are explained through photographs, drawings that "the curatorial team has culled [from] archives and architectural offices throughout the region," and models made especially for the show by students at the University of Miami and the Pontificia Universidad Católica in Santiago, Chile. The last are particularly large, built as sectional models that are lifted upon bases to eye level, allowing glances directly into the interior spaces:

[Model of Headquarters for the Banco de Londres y América del Sur, Buenos Aires (1966) by Clorinda Testa and SEPRA Arquitectos.]

[Model of Headquarters for the Banco de Londres y América del Sur, Buenos Aires (1966) by Clorinda Testa and SEPRA Arquitectos.] [Model of Cultural Center San Martin (1964) in Buenos Aires by Mario Roberto Alvarez.]

[Model of Cultural Center San Martin (1964) in Buenos Aires by Mario Roberto Alvarez.] [Model of Faculdade de Arquitectura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo (1969) by João Batista Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi.]

[Model of Faculdade de Arquitectura e Urbanismo, Universidade de São Paulo (1969) by João Batista Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi.] [Model of Edificio Altolar, Caracas (1966) by Jimmy Alcock.]

[Model of Edificio Altolar, Caracas (1966) by Jimmy Alcock.]Additionally, there is a side gallery "At Home with the Architect":

[Peering into the gallery devoted to houses for architects; the large photograph is Henry Klumb's own house (1950) in Puerto Rico.]

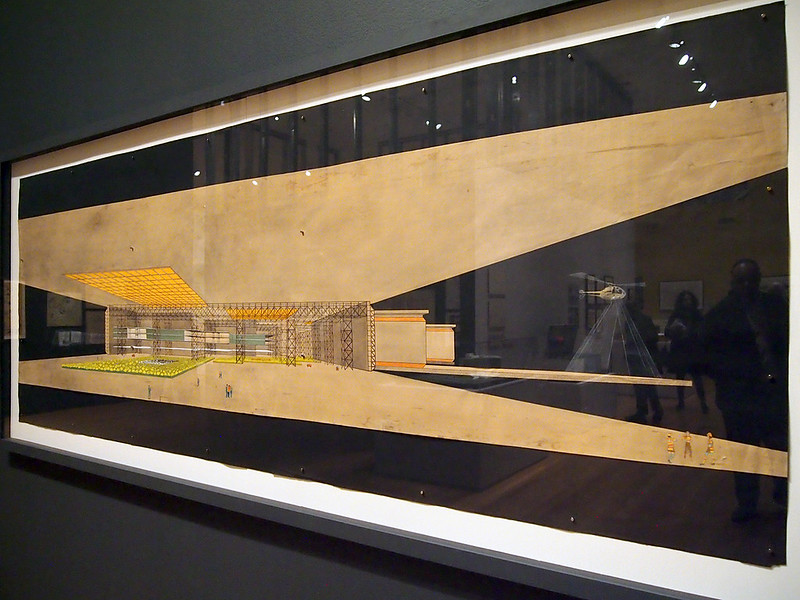

[Peering into the gallery devoted to houses for architects; the large photograph is Henry Klumb's own house (1950) in Puerto Rico.]The last two galleries are small ones, devoted to "Export":

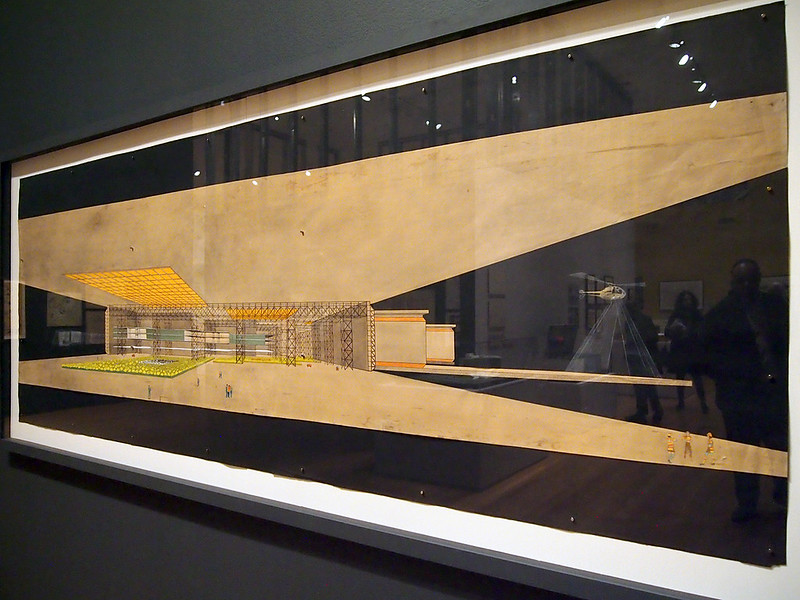

[Original model of Mexican Pavilion, Milan (1968) by Eduardo Terrazas.]

[Original model of Mexican Pavilion, Milan (1968) by Eduardo Terrazas.]And "Utopia":

[Project for the first city in Antarctica (1980-83) by Amancio Williams]

[Project for the first city in Antarctica (1980-83) by Amancio Williams]Outside the gallery, on the back of the wall where the "Development Equation" is mounted, are projected images from

MoMA's #ArquiMoMA Instagram Project, which asked people to share "images of buildings featured in the exhibition, to show their current context and how people see and use them today." The slowly changing images, much like the web page linked above, are a fitting addendum to the exhibition, since they further maintain a focus on the local, given that most photographs are probably taken by residents of Latin America. The photos also illustrate – as do the models and other media inside the exhibition proper – just how fresh and formally innovative the architecture produced in the years 1955 to 1980 was in the region. It's impossible to consider the current wave of formally exciting and socially innovative architecture in Latin America without acknowledging the work produced in the 25 years covered here. It's a shame it took MoMA so long to do so, but visitors are better off for the work of Bergdoll and his collaborators on compiling this exhaustive show, one I could only scratch the surface of here.