[Photo via

860-880 Lake Shore Drive]

Mies van der Rohe's

860-880 Lake Shore Drive apartments, shown above around the time of their completion in 1951, are two of the most influential towers in 20th-century architecture. Predating by seven years his Seagram Building in New York City, 860 and 880 consist of uniform facades with small, vertical I-beams in front of steel plates and clear glass.

[Facade detail | Photo via

860-880 Lake Shore Drive]

A basic expression of floor-to-ceiling glass and decorative steel meant to evoke the structural frame behind it subsequently became the go-to design for Mies and other architects in the 1960s and later, especially for office buildings. Today's urban environments of glass skins (now taut, with silicon joints rather than decorative projections) would be unthinkable without this trailblazing pair.

[All photographs of

Tower by John Hill]

860-880 are the source, and modern architecture is the subject, of Polish artist Monika Sosnowska's

Tower,

on display until October 25 at Hauser & Wirth on West 18th Street. The artist has taken the facade – everything in front of the structural steel, fireproofing and floors – built it at full scale and then distorted it beyond recognition. Well, almost beyond recognition.

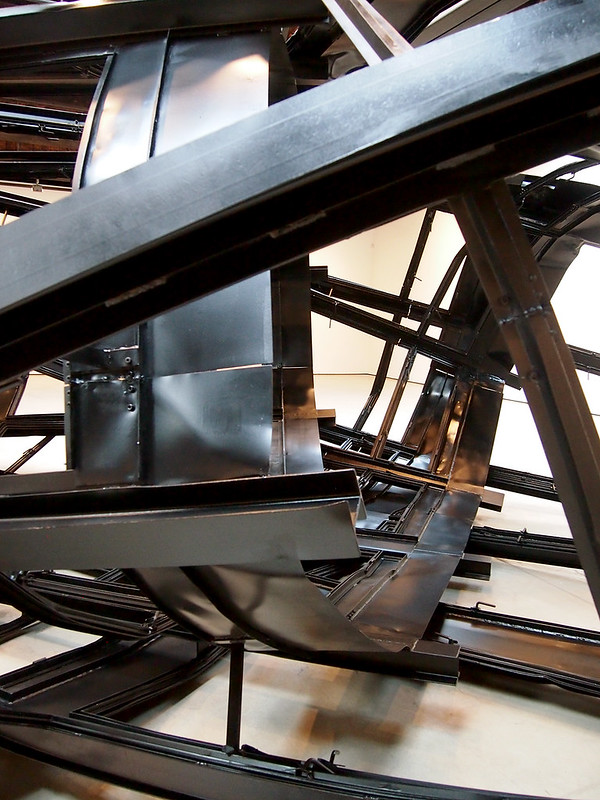

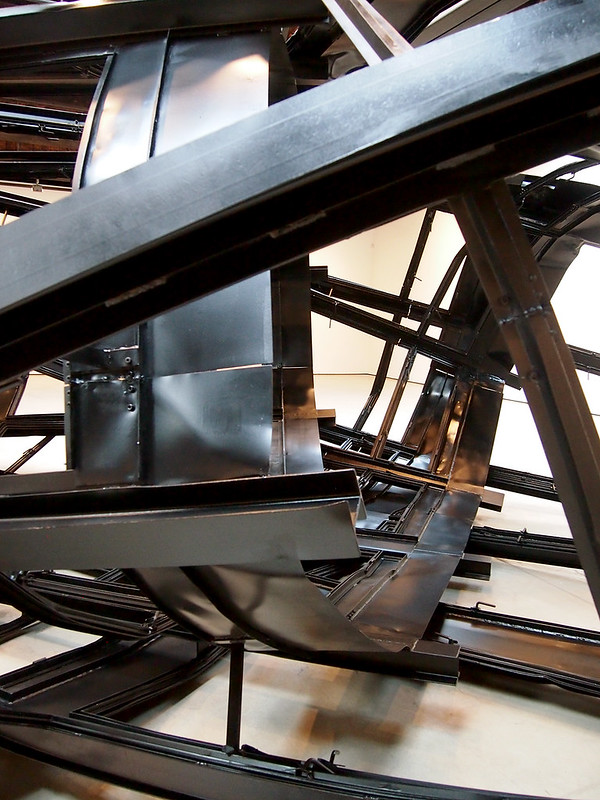

Walking into the large gallery space, the first view of

Tower is the one above; the 110-foot-long piece is so big that I could not capture it in a single photo. My first thought was "beached whale," and while I can't say if the artist intended such a resemblance, the form and the inversion of the subject (from vertical to horizontal) does give the impression that modern architecture is dead or dying, much like a whale washed ashore is dead or dying.

Tower

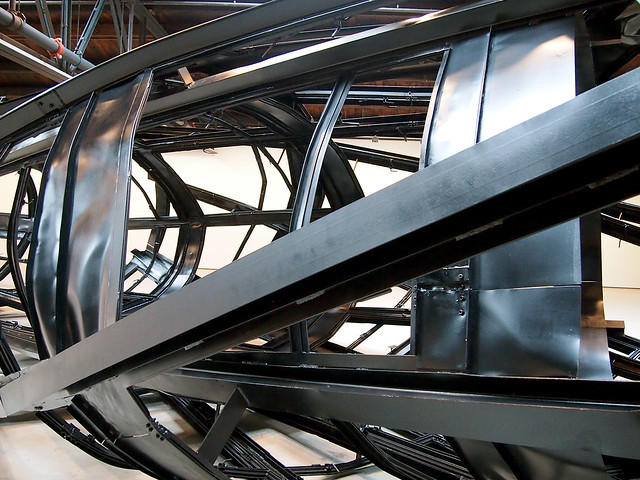

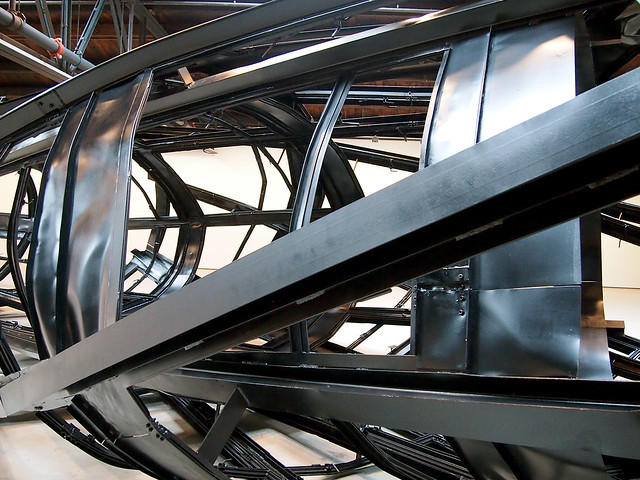

Tower's modules are those of the original facade, the rectangular window bays between the decorative I-beams, with a large pane of glass above a smaller, operable pane. Of course, glass is missing from the piece, but if we straighten out the bent construction in our minds, the regular, rectangular grid is there, vertical on one side (photos above and below) and horizontal on the other (top installation photo).

Comparing the top view of the installation to the one above – photos from alternate ends of the piece – shows the most distinctive experiences of the piece. Where the steel is coiled tightly, as in the above photo,

Tower is like a tube, a restricted view where the end is barely visible.

But at the other end (photo below), the steel unfurls, as if the tension of the coil at the other end could not be contained. Here, the piece exposes itself in all its gruesome complexity.

About halfway down the 110-foot length of the piece, the steel transitions from what I described as vertical to horizontal. This transition can be seen in the below photo, with the vertical windows on the right and the horizontal windows on the left (look for the intermediate mullion between large pane and operable pane to get a sense of the orientation).

Looking at the facade detail of 860-880 near the top of the post, one question that may arise is: Why is

Tower all black when Mies's original is black steel and gray aluminum? This is a good question, not only because Mies is quoted as saying "God is in the details" but because the pair of towers were replicated at 900-910 Lake Shore Drive with some minor changes, one of them being an all-black metal exterior. So with

Tower's all-black appearance, Sosnowska is referencing not only the original but also its copies, be it right across the street or elsewhere around the world.

It's easy to go on analyzing

Tower in terms of the architecture of modernism (or the destruction of architecture, à la 9/11, that the mangled form also brings to mind), but intellectual perspectives on the piece are not needed to appreciate it. The thing is so big and so gnarly that it just impresses out of its size and form: the way the pieces bend as well as the way they overlap each other; the way it occupies one half of the gallery, cutting a diagonal across the room and inviting visitors to walk around it; and the way it's hardly concerned with beauty or order.

Tower

Tower invites speculation about how it was made. While a book specifically on the piece will be released in November, one needn't see that to know it was a complicated and intensive undertaking, akin to constructing a building, both in terms of mechanical muscle and the coordination of labor needed to move the project from scale models to full size.

So if you're in New York City between now and October 25, be sure to head to Hauser & Wirth to take in Monika Sosnowska's

Tower to experience it for yourself.